Sagging through the dog days, the Dodgers needed a jolt. Luckily, they had an ideal jolter in their clubhouse. Reggie Smith wasn’t the same player he’d been even recently, his damaged shoulder leaving him unable to throw and limiting him to pinch-hitting duty in every one of his 20 appearances through mid-August. Dodgers trainer Bill Buhler began discussing Smith’s injury in retrograde terms, saying that it was back to where it had been during spring training, five months of rehab be damned. Smith, one of the team’s undisputed leaders, was visibly frustrated, unable to do much of anything to aid a winning cause. He had lost all three of the World Series in which he’d participated—with Boston in 1967 and with the Dodgers in 1977 and ’78—and now that he had a chance to rectify it, he couldn’t help but wonder whether he was a burden to the roster. This made him angry.

On August 25 at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, the 16-year veteran reached the limit of his ability to keep his frustration contained. He wasn’t in the lineup, of course, because he was never in the lineup. Hell, Smith had batted only three times in the two weeks since play resumed following the mid-season strike, whiffing twice and grounding into a double-play. Just over a month remained in the schedule, and despite having been on the active roster since opening day, he’d collected four hits all season. Of course he was angry. This may have explained why the guy who was already the least likely Dodger to abide an opponent’s shenanigans had so little tolerance when Pirates pitcher Pascual Pérez—a 24-year-old only recently recalled from Triple-A—nearly hit Dusty Baker in the first inning, then did hit Bill Russell in the sixth, then four batters later nearly hit Baker again, then actually did hit Baker one pitch after that. Dusty took it in stride and calmly headed toward first base, but on the bench Smith spun into a tizzy. “I’ll see you after the game,” he shouted toward the mound after Pérez struck out Steve Garvey to end the inning. The slender Pérez, 20 pounds lighter than Smith despite being two inches taller, was uncowed. “How about right now?” he responded.

“Reggie had that voice that carried a little better and a little louder,” recalled Jerry Reuss. “And Pérez was one of those guys who’d hear everything you’d say and respond to it.”

Smith was one of five Dodgers who grew up in or around Los Angeles, a product of Centennial High School in Compton. He was a switch-hitter with power, possessing (before his shoulder injury) one of the strongest outfield arms in the sport, not to mention one of the keenest minds. Smith was a big leaguer with Boston at age 22 and from the very beginning brought more intensity to a ballfield than some of his teammates knew how to handle. The catch was that he rarely cared whether he might be rubbing people the wrong way. Smith got into tiffs with the media and Red Sox management, and fought with teammate Bill Lee. When he intoned that racism was an issue in New England—primarily because racism was an issue in New England—a fan base that had already started to sour on his off-field drama doubled down. “Bottles were thrown at my house,” Smith said. “My son heard nasty things said about me in school. Someone scratched my car with a key. I was called all kinds of names. Well, Boston is a racist city.”

“Reggie was a proud man, and he was scarred by the Boston experience, there’s no question about it,” reflected reporter Chris Mortensen. “I remember thinking that somebody pissed off the wrong guy.”

Never mind that in six full seasons with the Red Sox Smith was runner-up for Rookie of the Year, made two All-Star appearances, earned a Gold Glove, and picked up MVP votes four times; Boston couldn’t unload him quickly enough. Five days after the 1973 World Series, the Red Sox flipped him to St. Louis for Bernie Carbo and Rick Wise.

Immediately feeling more comfortable in the harder-edged National League, the outfielder said that American Leaguers “took my aggressiveness as being mean”—a sentiment valid only when his aggressiveness wasn’t actually intended to be mean. With one of the most intimidating men in baseball, it was sometimes difficult to tell. Speaking about Smith’s short fuse, Dave Goltz said that his teammate “can go off the deep end real quick for a very little thing.” Jerry Reuss compared Smith to Reggie Jackson. “If you have a Reggie bar in New York, you open it up and it tells you how good it is,” he said. “If you have a Reggie bar here, you open it up and it punches you.”

Smith earned an All-Star berth in each of his two full seasons with St. Louis but injured his left shoulder on the second day of the 1976 campaign and batted just .218 thereafter. He had been in a dispute with Cardinals brass over deferred salary payments, and the team seized his decline as an excuse to rid themselves of a headache, sending him on June 15, 1976, to Los Angeles in a deadline deal involving Joe Ferguson. Despite rumors out of St. Louis that Smith hadn’t been injured as severely as he claimed (started, said Smith, by the Cardinals themselves), Dodgers doctor Frank Jobe surgically repaired loose cartilage in the outfielder’s left shoulder after the season.

Smith might not have seemed like the ideal target for Tommy Lasorda’s brand of feel-good motivation, but when he arrived in Los Angeles, it worked. “Lasorda came to me and said, ‘I need you,’” the outfielder recalled. “No one in baseball ever said that to me.” Smith became one of LA’s quartet of 30-homer hitters in 1977 and led the team in home runs in 1978, finishing fourth in the NL MVP vote both times as the Dodgers won back-to-back National League pennants. Bill Russell called Smith “the difference between first and second place for us.” Dusty Baker positioned the outfielder as “the second-best player I ever played with,” behind only Hank Aaron.

Then Smith’s familiar bugbears arose. As the Dodgers struggled in 1979, losing 31 of 41 to enter the All-Star break dead last in the NL West, Smith scuffled similarly. Hitting .163 well into May was one thing, but getting into a public contract battle with Al Campanis opened an avenue of dialogue that people throughout the organization would have preferred remain shut. Smith proclaimed that he had signed his contract with assurances that among the Dodgers, only Steve Garvey would ever receive a higher salary. At the time of his objection, Smith’s paycheck ranked fourth on the team. He complained about being lied to, then surprised everybody by adding that “I can’t seem to find the concentration this year,” while admitting that “my mind is elsewhere.” As if to up the shock value even further, he then claimed that, surrounded by what he perceived as acceptance of losing, “it is very difficult for me to care whether we win or not.”

Talking openly of retirement, Smith missed meetings and BP sessions. This did not sit well in the clubhouse. Teammates openly labeled him a quitter, anonymously suggesting in reports in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner and the Long Beach Independent Press-Telegram that the Dodgers would be well served by ridding themselves of his baggage. That July, Smith called a clubhouse meeting at Dodger Stadium, during which he spent the better part of an hour shouting about the injustice in his midst. The very next day he reinjured his ankle and collected only a single at-bat through the rest of the season.

“Reggie was a force in every way, on the field and off the field,” said reporter Lyle Spencer. “He had high standards and great integrity. He was a guy who didn’t have the capacity to be political and was totally honest all the time. That was seen as being difficult, but in reality it was just his nature, being honest. He would never back down from his point of view, and that would occasionally get him in trouble.”

Players who make a lot of noise while failing to perform rarely find steady employment. As Smith proved in 1980, however, solid character and a robust stat line will mitigate all manner of outburst. His early season was a return to form: a .328 batting average, 15 homers, and 51 RBIs were good enough to make his seventh All-Star team as the Dodgers entered the break with the most wins in the National League. Two weeks later, however, Smith’s shoulder acted up again, the latest flaring of a chronic injury that made the joint pop out of place, and would ultimately require the reconstructive surgery that not only wiped out the remainder of Smith’s 1980 season but limited him to pinch-hitting duty in 1981. (After the procedure, Smith was visited in the hospital by Jerry Reuss and Don Stanhouse, who borrowed white jackets from the staff and taped paper towels across their faces in lieu of surgical masks. The ersatz doctors laid out a cornucopia of fried chicken, barbecued ribs, and a bottle of scotch atop a gurney, covered it with a blanket, and entered the outfielder’s room as if important medical business was at hand. Smith immediately burst into laughter, even as his family members wondered what the hell was going on. There’s something to be said for bedside manner, but the pitchers ended up feeding Smith so much scotch that his blood-sugar levels destabilized and he had to remain hospitalized for an extra day. “It wasn’t our nature to be low-key,” smiled Reuss, looking back.)

Smith didn’t have to throw a baseball, however, to put a scare into a hothead like Pascual Pérez. As he lobbed threats toward the Pirates pitcher throughout the inning, it didn’t bother Smith a bit that Pittsburgh—featuring enormous players like Dave Parker, Jim Bibby, and John Candelaria—was the league’s most physically intimidating team. When Pérez pointed toward the grandstand—an obvious invitation to meet out of sight, in the stadium bowels—Smith didn’t hesitate. Each man raced for his dugout stairs, which led to the interior hallway that connected the clubhouses. Players from both teams scrambled to follow, the benches emptying not toward the field but away from it, a reverse brawl, spikes echoing off the concrete floor. Baker, far from the action at first base, sprinted to catch up to the rest of the Dodgers, shoving past Lasorda “like a wild buffalo,” the manager said later.

In the press box, reporters were baffled. Knowing something was afoot but having little idea what it might be, a passel of media members hopped an elevator for some on-the-scene reporting. Unfortunately for them, the elevator shaft, located directly between the clubhouses, opened onto the spot toward which, at that very moment, each team was charging.

“On one side is Pascual Pérez and the Pirates, who were the hugest team in history,” recalled Peter Schmuck of the Orange County Register. “Pérez has a bat in his hand. We look the other way, and here’s Reggie Smith and the Dodgers coming out of this other hallway. We’re standing right in between them.” Pirates manager Chuck Tanner screamed for security to clear out the reporters, more of whom were emerging from a nearby stairwell. He didn’t have to ask twice. “It was like, push the elevator button!” said Schmuck. “Get that elevator back!”

In the hallway, which was no more than 10 feet wide, Willie Stargell and Bill Madlock blocked Smith’s path to Pérez. That might not have been a bad thing. Pérez raised his bat as if to swing, but was stymied when teammate Bill Robinson grabbed his arm. Smith went straight to negotiation. “Pops,” he said, referring to Stargell by his nickname, “this has nothing to do with me and you, so get out of the way.” Stargell, though, was captain of the Pirates for good reason. “Come on,” he said sternly to Smith, “there ain’t gonna be none of that.”

Smith was uncowed. “If I have to go through you, Pops,” he snarled, “I’m going to go through you.” Whatever Smith’s purpose, however, no matter how intent he was on getting a piece of Pirate, the hallway was simply too tight for a group brawl. Amid the crush of bodies, the outfielder couldn’t so much as effectively draw his fist back, let alone throw a punch. Never mind that the Dodgers were wildly outmanned when it came to BMI—“a bunch of little guys trying to look over a fence,” is how Dave Stewart put it. All Dusty Baker could think about was the five-foot-ten Garvey, the five-foot-ten Cey, and the five-foot-nine Lopes going up against an NFL-sized front. Even the best fighter of the bunch, Smith himself, was markedly smaller than fully half of Pittsburgh’s roster.

“It was like a scene from Braveheart, little guys against big guys,” said Garvey, looking back. “It had no future. You’re thinking to yourself, ‘I wasn’t involved in this. I’m going to help my team, but this is crazy.’”

“All the years we’d been in that stadium, we thought those hallways were somewhat wide,” recalled Rick Monday. “It’s amazing how small they got in a hurry.” Those at the front lines ended up nose to nose with the opposition, but things pretty much ended there. Pérez stayed safely behind his wall of teammates, and before long players coaxed each other back toward the field. “Let’s put it this way,” said Monday. “Air traffic controllers don’t let jets get that close.”

The Dodgers, ahead 6–1 at the time of the incident, held on for a 9–7 victory—nobody was even ejected—in the second game of what would become a five-game winning streak, LA’s longest such stretch since mid-May. Maybe Smith was on to something.

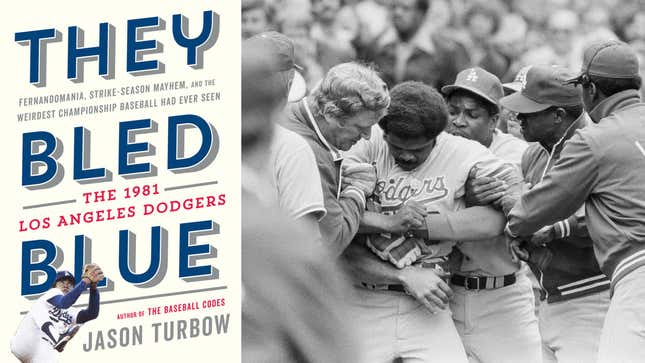

Excerpted from THEY BLED BLUE: Fernandomania, Strike-Season Mayhem, and the Weirdest Championship Baseball Had Ever Seen: The 1981 Los Angeles Dodgers by Jason Turbow. Copyright © 2019 by Jason Turbow. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.