Ascape Audio and the economics of making headphones in America

Designed, not made, in Detroit.

Ascape Audio's home page proudly proclaims "Designed in Detroit," but at this point it's not helping business.

"It hasn't made any goddamn impact," marketing director Dean Clancy said. "I want to put that in as many places as possible, because regardless of how it impacts our sales, I just want people to know we're doing it here," he said.

"Designed in Detroit" they may be, but economics makes manufacturing Ascape's earbuds in the Motor City impossible. President Paul Schrems estimated it'd take at least $5 million to build a factory and staff it, so the company has offshore-manufacturing contracts for the wireless earbuds it designs in the D. "These things I wanna make are not made here," Schrems told me recently.

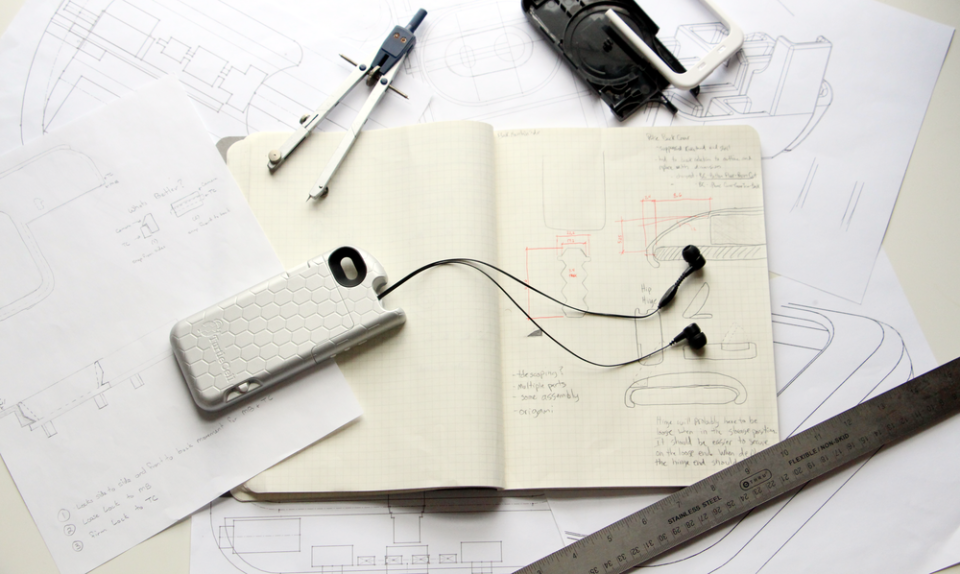

Ascape's next project is the Ascend-2, a pair of earbuds with a twist-to-lock feature to keep them from falling out during a run or sweaty workout, promising better comfort and audio quality than the previous iteration. Like Apple's AirPods, they'll come with a case that doubles as a charger and extends battery life. "No [local] manufacturing partner is motivated to make something like that," he said.

Part of that is because Michigan, and the US in general, doesn't have a supply chain set up for making consumer electronics at scale the way it does automobiles. Components and raw materials have to be sourced offshore, and currently there's a dearth of talent required to oversee production and assembly once the injection molds start pumping out minuscule parts.

In a recent fireside chat, Apple CEO Tim Cook told Fortune that the reason Apple works with China is because the country's people excel in highly skilled tooling environments and labor-intensive vocations. "In the US you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I'm not sure we could fill the room," he commented. "In China, you could fill multiple football fields."

"It doesn't even make sense to do it over here anymore," Schrems said.

If the largest corporation in the history of the world can't build phones and earbuds in America, how can you expect a five-man team from Detroit to do the same?

Ascape started life under a different name, shortly before Schrems graduated from the University of Michigan in 2011. He had a 40-minute hike from where he parked his car to the main building on campus and got tired of spending half his walk straightening out his headphone cables. "Everything tangles; it's just a law of cables," Schrems said. As an engineering student, he figured there had to be a better way.

Being on campus meant easy access to 3D printers, so Schrems spent his spare time mocking up designs for what would eventually be his first product, TurtleCell. It was an iPhone battery case with a spring-loaded mechanism that automatically retracted the headphone cable when not in use.

Along with co-founders Nick Turnbull and Jeremy Lindlbauer, Schrems twice took the project to Accelerate Michigan, a startup competition, and each time walked away with a $10,000 prize for the People's Choice category. The team was featured in the Detroit Free Press and soon got a phone call from a company in nearby Auburn Hills that wanted to license TurtleCell.

They signed a licensing agreement and eventually produced almost 100,000 cases, selling them online. The fledgling company hired additional help along the way, with Clancy being the first full-time employee and the local partner trying to get TurtleCell into retail. "The key word there is 'tried,'" Schrems said.

Retailers didn't trust retractable products because they'd been burned before. Mechanisms break, customers complain and the store is left with crates of unsold-and-returned merchandise. It's hard to blame their reticence. Schrems went as far as to make a machine to test the mechanism's mettle, certifying the retractor's use up to 10,000 times. But nothing would change the big box stores' minds.

After that, things started going south with their local partner, and Schrems had to fire the entire team. He was in China scouting suppliers when he let Clancy go. When Schrems mentioned the layoffs during our interview, Clancy turned to him, laughing, "Thanks, sweetie."

Clancy is a little brash, with a punk rock attitude that stems from playing guitar and growing up in Ann Arbor, near Iggy Pop's hometown. He's more outwardly opinionated than Schrems and has a fondness for four-letter words that his business partner can't match.

The pair complement each other well, socially and professionally. Clancy does a lot of the creative work with branding and marketing while Schrems handles manufacturer relationships and other business-related duties as company president. "The stuff I'm not good at, Dean's good at," Schrems said.

Luckily for Clancy, he and Schrems hit it off in their short time together, and in 2016, less than a year after the TurtleCell ordeal, the pair co-founded Ascape Audio.

Because they're designing a product that's atypical for Michigan, the talent pool is limited. Ascape currently has around five employees, with the pair bringing in friends short term to fill in the gaps. Clancy hopes they don't have to do that for much longer but admitted that at this stage of the business, it's a necessary evil.

Just outside Ann Arbor is Saline, where a few electronics manufacturers in Michigan reside -- but they exclusively make medical devices. Schrems also reached out to shops in Tennessee and California with little success. Within a month, he realized that to bring Ascape's product to market as envisioned, he'd need to start looking offshore. "The simple fact of the matter is no one makes headphones in America anymore," he said.

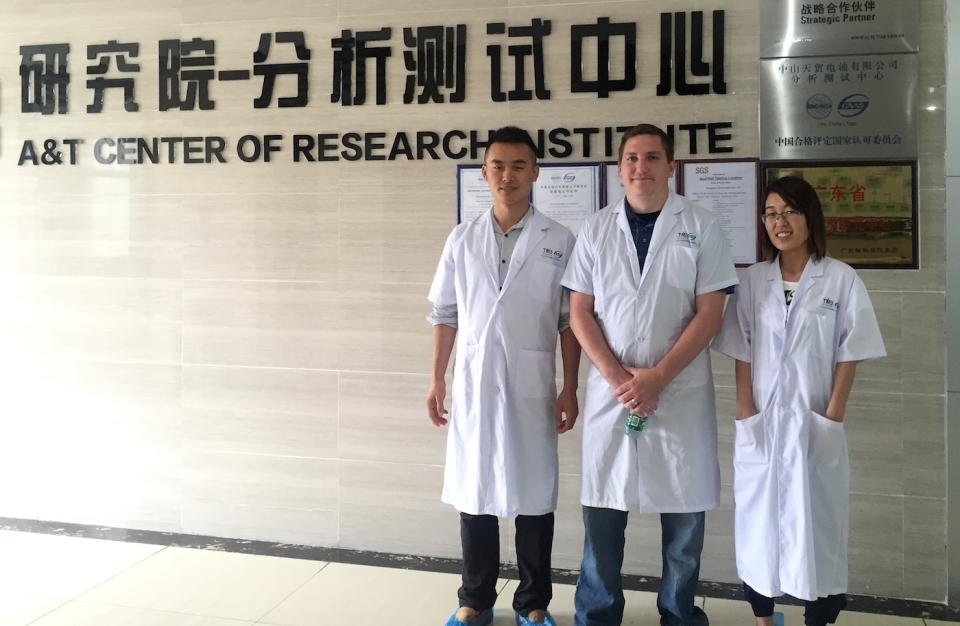

At one Asian battery factory, Schrems said everything was "crystal clean" and modern. Later that day, he sat in a boardroom alongside his translator and another person he'd brought on the trip. Across the 120-seat conference table sat eight people from the manufacturer. One wall had a waterfall built into it. He couldn't figure out why the cavernous boardroom had to be so big and elaborate, so he asked. They told him that "when Samsung shows up, they bring 80 people."

On another tour, Schrems visited a different battery plant. Compared to the Samsung supplier, he said, it was filthy and inefficient. There wasn't any automation, and every task was performed by hand. But the prices were cheaper than other suppliers'. By a lot. In the end, Schrems went with the cleaner plant, picking batteries that were already in production and, as such, less expensive.

Almost every company that makes headphones is doing it in Asia because the economics are better. Even Grado, which famously manufactures its shells in the US and assembles headphones in Brooklyn, sources its internal parts from Asia.

"It's the American manufacturers, manufacturing companies, just choosing what products they want to make and which ones are profitable for them to make."

When Schrems was still working on TurtleCell, he wanted to do a small manufacturing run to make sure the design for the battery pack was up to snuff. He reached out to Midwest Mold, a local tool shop in Detroit suburb Roseville.

The company looked over Schrems' patents and estimated soft tooling would cost $55,000 just for one piece of the case. Hard tooling would cost an additional $80,000, and to build the entire battery case it would be at least $200,000 in up-front costs. Working with a Chinese partner would only cost Ascape $72,000. When Schrems told the local supplier how much he'd been quoted by the Chinese company, "they just laughed," he said.

If the price of domestic manufacturing was only slightly higher than outsourcing, Schrems wouldn't think twice about making Ascape products in Michigan. The control over the entire process would be a lot better, and he wouldn't have to deal with headaches like language and social barriers every time he needed to communicate with the supplier. "If I could drive an hour to the place where it was getting made instead of having to schedule a two-week trip, and speak to the guy who's actually gonna run the coding machine, it would be so much easier," Schrems said.

"You get shit for it too. Trust me," Clancy said. "It's like ... you think we don't wanna do it here?"

"We'd love to," Schrems added. "It's the American manufacturers, manufacturing companies, just choosing what products they want to make and which ones are profitable for them to make." In the end, Ascape paid Midwest Mold $5,000 in consulting fees to ensure its tooling was correct before sending the order to China.

It's easy to make life difficult for yourself when working with offshore suppliers. There's the language barrier, sure, but then there are the cultural hurdles. "Over there, they're not as aggressive about telling you that you're doing something wrong," he said. "You're the customer; you're always right. So they'll let you make mistakes without telling you."

He brought up the example in Malcolm Gladwell's book Outliers: One whole chapter details why Korea Air had so many crashes in the '80s and '90s. It was due to communication issues, because the cockpit crew members weren't effectively telling one another or the control tower when something was definitely incorrect, in a forceful way. "I actually liked finding manufacturers who would tell me I'm wrong," he said.

It typically takes two to three weeks for Ascape to go from making the initial order to getting a mock-up. "That's pretty quick," Schrems said. That doesn't count the weeks of back-and-forth emails hashing out the engineering and design process itself though. He admitted that even with his experience and degrees (a bachelor's in mechanical engineering and master's in electrical engineering systems), there were still facets of the real-world process he wasn't prepared for. "[Eastern companies] have been doing it for years, right?" he asked. "I had to learn through making mistakes of what can go wrong with the product."

The TurtleCell designed for the iPhone 6 originally had a kickstand, because the marketing team demanded it. Since there wasn't anything similar to a battery case with retractable earbuds and a kickstand, getting the tooling right was a nightmare. And expensive. The tooling supplier quit before production was finished, and the fledgling accessory company had to shell out extra money just so the manufacturer would complete the job. Schrems estimated it delayed shipment to customers by at least two months.

Ascape has been working on the Kickstarter campaign for the Ascend-2 since last October. A lot of the labor has been shooting lifestyle photos, filming a Facebook commercial and the pitch video, and rendering new models of the earbuds. It's difficult to do that when the product you're selling is aimed at folks with active lifestyles and you're in the height of one of Michigan's infamous winters.

The plan is to launch between the end of April and the beginning of May and have the initial goal set low enough that the campaign is fully funded within the first few days. Should that happen, it means Ascape will make the Kickstarter homepage and start generating organic interest. It also means that any money raised beyond the artificially low goal will stay in Ascape's coffers.

Schrems said Kickstarter serves a few purposes: It's an "awareness generator," and the company will help fund projects launching on the platform. Ascape would've put the first Ascend on Kickstarter, but the team thought it was too late to the fully wireless earbud craze and wouldn't generate any interest. Looking back, Schrems said it would've cut Ascape's digital-marketing costs significantly and the first Ascend could've launched sooner.

The up-front costs for the Ascend-2 are much higher than for the previous model. Since there aren't local angel investors or a licensor involved this time, Ascape needs as much cash on hand as possible to start production and buying inventory. Selling pre-orders on a crowdfunding website is an easy way to generate capital. Plus, courting investors would take more time. Schrems said it's better to go to customers directly first and then once you have sales figures, let the investors follow.

While there have been a few organic multimillion-dollar campaigns, Schrems said they've "rarely" ever broken $1.5 million in pledges. And that if one has pulled in more than that amount, there was definitely a marketing agency working behind the scenes.

Ascape's marketing agency is Jellop, which boasts it's helped raise almost $210 million across 439 projects, including the $13 million campaign for Pebble's second activity tracker. "If you're looking to pump up your campaign, talk to them," Pebble's Benjamin Bryant writes on Jellop's website. Jellop typically waits until a campaign is under way to offer its help, but the firm reached out to Ascape months in advance.

"If the Kickstarter goes wildly successful, like many of them do, then we can make these and become an acquisition target."

Clancy and Schrems wouldn't divulge how much the pre-launch social media ad campaign costs, but it sounded like it wasn't cheap. "With the amount of money we're spending on the advertising pre-campaign..." Schrems said before catching himself. "If we don't [fully fund], that's gonna be a fucking..." Clancy mused, before Schrems cut him off. "Maybe we shouldn't be saying all this." Suffice to say, Jellop has made a significant investment, and Ascape will dominate your News Feed in the run-up to launch.

"If the Kickstarter goes wildly successful, like many of them do, then we can make these and become an acquisition target," Schrems said. If it gets mediocre results, Schrems said the plan is to take their self-written 50-page patent and proof of sales and, in a word, sell out to a big player in the space.

It's happened before. Revols launched its campaign for form-fitting wireless earbuds in Nov. 2015 and its $100,000 goal was fully funded in under seven hours. By Jan. 2016 the company had raised $2.5 million with more than 10,000 backers. Last Dec., the company was bought by Logitech.

It's pretty clear Schrems and Clancy wouldn't mind being gobbled up by a larger company. But if that doesn't happen, the pair would be happy to run a successful business for a few years and put a bit of Motown in people's ears, regardless of what music they're listening to.

Detroiters show Ascape a lot of love. Clancy said that startups in the city benefit from people wanting to see it bounce back and throwing support behind those efforts.

Texas-founded watchmaker Shinola recently got into the headphone space with a collection of headphones and in-ear monitors named after the historic Canfield district in Detroit. Prices originally ran between $195 and $650 but have since dropped to $450 for the most expensive model. The company also offers a $2,500 turntable and $1,500 speakers.

"People are like, 'Fuck, yeah. You're not Shinola.'"

Shinola came under fire for the Canfield launch. Reviewers said the products were too expensive and the sound didn't live up to the price while the Federal Trade Commission put Shinola in the crosshairs for its not-entirely-true "where American is made" marketing efforts. Others have complained that Shinola is an opportunistic outside company mining Detroit's history and hardships to make a profit. Shinola's in-ear monitors are produced by Campfire while its headphones are "designed, tuned and tested" in Detroit, but like Ascape's models, they're manufactured offshore.

"People are like, 'Fuck, yeah. You're not Shinola,'" Clancy bragged. "The support, for me, speaks a lot to our aspiration and our potential. I don't think we'll get any backlash."

Clancy said that Ascape isn't the typical team heading to crowdfunding platforms with a prototype and a twinkle in its eye. "We're an established company," he said. "We've kind of done this before. What we need is some credibility on Kickstarter to prove we're not just another idea."

Despite all the unforeseen hardships and trial and error, as late twentysomethings, Clancy and Schrems wouldn't want to do anything else for a living.

"[We've been] doing it on our own and being just a group of fucking guys that wanna have fun and make money at the same time, and survive," Schrems said.

When I first met Clancy and Schrems, the former was wearing a naval captain's hat and sunglasses, hawking his wares to sweaty, sunburned, dust-covered concertgoers at Detroit's Mo Pop Festival last July. Clancy assembled their display tables in his garage, and a lot of the engineering work on the Ascend-2s was done in Schrems' garage. It's been enjoyable for them, and they like the bootstrappiness of it all.

Clancy reminisced about breaking into the backstage area when Queens of the Stone Age played the Fox Theatre last fall. He hung out with guitarist Dean Fertita (who also plays in Jack White's The Dead Weather), bonding over shoptalk and what it was like growing up in the area. Fertita hails from Royal Oak, where Schrems lives currently, and as such has become a hero for local musicians. "I hope someday we get to be that, in a weird way," Clancy said, "for other people who wanna do hardware startups in Detroit."