Instead of celebrating last weekend face down in a sombrero full of tequila-spiked OJ and a few lime wedges, 71 racing teams with one set of tires each and no support crews began Cinco De Mayo — and this year's 35th running of the One Lap of America — by hitting the wet skid pad at Tire Rack's headquarters in South Bend, Ind. There were Porsches, Vettes, Camaros and BMWs galore. There was a Miata, a vintage NSX, a Honda S2000 and even an old VW Rabbit. There were GTIs, the odd Evo and, oh yeah, six Toyotas, a couple of Vipers and a couple of GTRs.

When the skidding stopped, a 2011 BMW 1M emerged triumphant and led the pack out into the heartland, where it will spend 5,000 miles this week hitting road courses, dragstrips and time trials at tracks as far west as Denver, as south as Fort Worth and then New Orleans. From there, it will barrel north through Mississippi, Alabama, Nashville, Kentucky and back home again to Tire Rack in Indiana. Twenty events, eight venues, with a three-hour window for each event.

It's a nonstop, no-sleep, one-week road trip comprising 150-ish friends and brothers, partiers and pro racing drivers, spouses and other family-member combo packs. Some will never speak to each other again, some might end up divorced, some might get married.

All of them are nuts.

I know this because I made three laps. Three laps I will never forget.

LAP ONE: 1984

Vehicle: 1984 Dodge Van

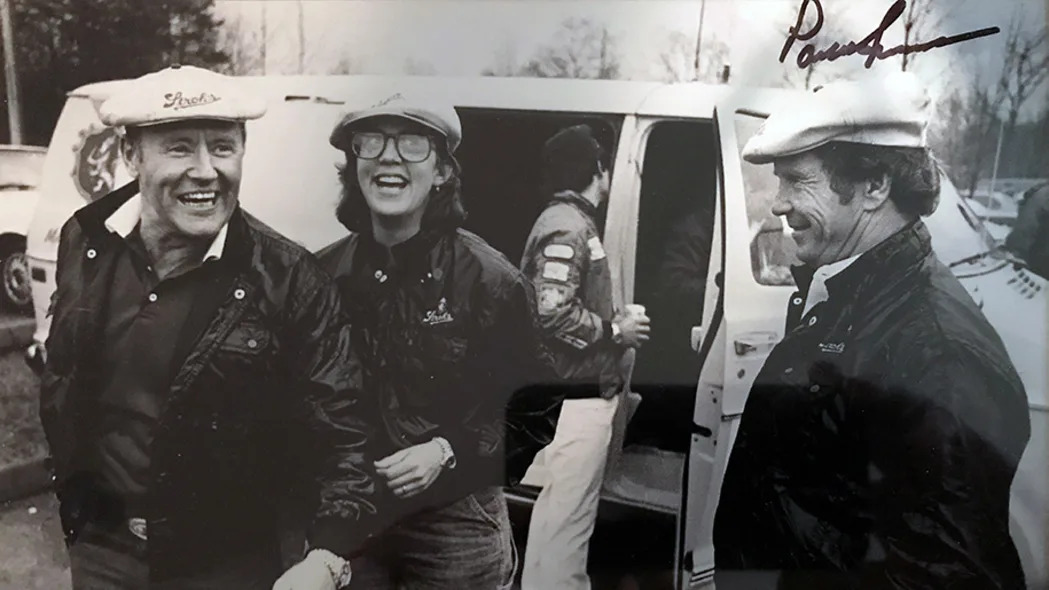

Team #0: Jean Lindamood (Jennings), Walker Evans, Parnelli Jones

I was present for the inaugural 1984 One Lap of America because I worked at Car and Driver back then and so did Brock Yates. He was the guy who came up with the clandestine, illegal, unsanctioned Cannonball Baker Sea-to-Shining-Sea Memorial Trophy Dash from Connecticut to Redondo Beach, Calif. It ran five times in the 1970s, with Yates joining Dan Gurney in a Ferrari Daytona for the second run. They won, Gurney insisting that "at no time did we exceed 175 miles per hour."

One Lap was born of Cannonball nostalgia (read: Brock was bored), and I was beyond game for it. After securing a van from Dodge and two giant decals for the van sides, along with $5,000 in sponsorship from local Detroit Stroh's Brewery, I coaxed my friend, nine-time Baja 1000 winner Walker Evans, into running One Lap by suggesting he didn't have a hair on his ass if he refused. Then I suggested that if he didn't get his best friend and longtime road trip buddy, Parnelli Jones, to go with us, I would actually have to drive the van, too. That took the tinkle out of him. Parnelli was game, and we agreed to meet at the starting ramp in Darien, Conn., where Yates had arranged for a couple of women in bikinis to wrestle in a kids' swimming pool full of Jell-O. Did I say this was 1984? Right.

Walker split up the sponsorship cash into lots of little piles of Benjamins, then hid them all over the van, a habit he picked up from all his desert racing in Mexico. I had a cooler full of salad stuff and drinks that I packed behind the front captain's chairs, part of extensive van modifications Prince Corporation and ASC had made for our comfort.

Parnelli and Walker had arrived at the start early so we'd be ready to lead off as Car #0. They weren't finished outfitting the van.

"What are you holding?" I asked them.

"We figured we could use one of these for trash," said Parnelli, showing me two small trash bins. "The other one we can put a liner in and you can pee in it so we won't have to stop. We can tie up the bag and throw it out the window."

We didn't have cellphones back then, so no one could rescue me.

Yates recorded every entrant's odo reading, He made us all sign waivers and promise not to exceed the national 55-mph speed limit, and then had the queen of the Supremes, Diana Ross, flag the event off. It was the only elegant moment of the week.

We hit a rhythm right away. Parnelli and Walker rode in the front, and I had my own captain's chair and a side table in the back from which I made us lunch, read the maps and barked navigational orders, Like, "WHY ARE YOU GETTING OFF AT THIS EXIT?!?" The only time I rode in the front seat was for the night shift, when Parnelli would take the wheel and Walker would crawl into a bunk installed across the back of the van's cargo area. They switched seats without stopping. Walker would stand up, Parnelli would slide in under him, and Walker would sidestep right and go to bed.

It was their unchanging routine, and this would be their nightly exchange:

Walker (in singsong voice): "Parnelli, tell me a bedtime story."

Parnelli: "$%^& YOU!"

Walker (in singsong voice): "That's my favorite one."

Every. Single. Night.

The only real problem — other than the fact that neither listened to music, just filthy truck-stop joke tapes, and that they never let me drive — was that they couldn't understand that there was no way to figure out how to win. We had a 9,000-mile route map with big turns in four corners of the country — Boston, Seattle, San Diego and Miami. There was one 24-hour layover at the Portofino Inn in Redondo Beach.

We just had to get through eight marked checkpoints between the start/finish, and make it to the end where our final odo readings were recorded and matched against the total (SECRET) mileage of the entire route, as recorded by Brock and his great buddy Bill Baker in their initial 8,704.8-mile prerun.

My two crazy competitive teammates endlessly tried to work this out on paper. They had me adding up on yellow legal pads the map mileage of every segment of the total route to come up with some total mileage bogey. As we reached our halfway point in Redondo, our exit off the 405 was closed, throwing us off the "official" route, and they both freaked out. Parnelli decided we needed to unwind the extra miles by driving around Redondo Beach backward at 2 a.m. for about an hour until they'd convinced themselves we'd "fixed it."

We didn't win; we placed 18th out of 71 finishers.

But wait.

At my 1997 wedding in Geneva, Switzerland, a very tipsy Baker offered a hilarious roast of a toast, then grew somber and weepily admitted that the four guys from Vermont in the 1984 Chevy station wagon hadn't really won the 1984 One Lap. "It was Parnelli and Walker and Jean," he said. "But we decided that they didn't really need to win."

LAP TWO: 1985

Vehicle: 1985 Audi Quattro

Team #0: Jean Lindamood (Jennings), Nicole Ouimet, Ty Holmquist

Lulled by the lackadaisical vacation nature of the first One Lap, I re-upped for #2. The second One Lap was a more serious, more wintry affair, beginning with a rough March 1 start in downtown Detroit. The 80-car field was staged in front of the soaring Renaissance Center. Somehow, a Porta Potty was stolen from Benihana owner Rocky Aoki's 1959 Rolls-Royce Silver Wraith while it was parked in line, waiting for the green flag. Local Detroit booster Emily Gail's entire 1985 Lincoln Continental was stolen from the Renaissance Center garage where she'd left it running (?!?), its rear end plastered with "Say Nice Things About Detroit!" bumper stickers.

I led the way in a borrowed Audi Quattro with teammate Nicole Ouimet, a teensy French Canadian WRC rally driver for the factory Dacia team out of Romania. Our first task awaited 300 miles north across the Mackinac Bridge in the middle of a blizzard in Michigan's Upper Peninsula.

Brock had thrown out the "Guess Brock's Total Mileage" part of the equation and added four special road sections along the route where we had to manage our time and change speed according to last-minute handout instructions. My ringer of a driver and I both sucked at the confusing Time-Speed-Distance high math, so we hired a pro navigator from California, a guy who'd won a cross-country race doing these TSD equations the whole way. He got us lost the minute we hit the U.P., which meant we were doomed.

Over the course of the next eight days, there would be three more TSD stages — one the very next night in Kalispell, Mont. — and we immediately began to plot his demise as we drove 1,400-plus miles all night and day and some more night through an endless blizzard, at a very high rate of speed. With a couple of hours left to check in at Kalispell, we drove through the howling storm and found the ramp gates to I-90 closed and padlocked.

We had an Audi Quattro, a real WRC rally driver on a mission, and it was our only chance to make up for the disaster in Michigan. So, Nicole drove around the gate and headed west to Kalispell. At about 120 mph. Until the police pulled us over.

I don't know who was madder, the 90-pound girl shrieking in French, or the cop. I convinced Nicole to get in the backseat with the banished navigator, and I convinced the cop that I would drive us to the nearest hotel. A lie. I drove parallel to the freeway until it looked safe for her to take the wheel and press on. At about 120.

I don't think five of the 78 One Lap cars made it to Kalispell. Those that didn't convinced Brock to throw out that stage. We, in the meantime, eventually decided to throw out our navigator as soon as we could.

One other story of note, that of Car #5, the 1984 Cadillac Limo of Jim Bardia and his teammates Steve Behr and Dick Gilmartin. Gilmartin started the event with his leg in a cast, so he spent almost the entire drive wrapped in fur rugs and propped up in the back of Bardia's limo. Somewhere in the middle of the night in the middle of the mountains, just into northern California, the Limo made a pit stop. Gas was pumped, guys hit the head, the bill was paid and off they went, down the coast to Sears Point where we would be ceremoniously lapping the track.

And then Gilmartin came out of the bathroom. No limo. He thought they were pranking him.

The gas station closed and the kid running it took Gilmartin to an all-night diner in Redding where the cook fed him, loaned him money and found him an early-morning flight to LAX. Bardia and Behr never noticed he was missing until hours later when they checked in at Sears Point. The resourceful Gilmartin grabbed a cab from LAX to the Portofino and was waiting at a picnic table when the limo rolled up and threw open a door for him.

We made good our threat, bounced our navigator in New Orleans and finished in Detroit in 11th place.

LAP THREE: 1994

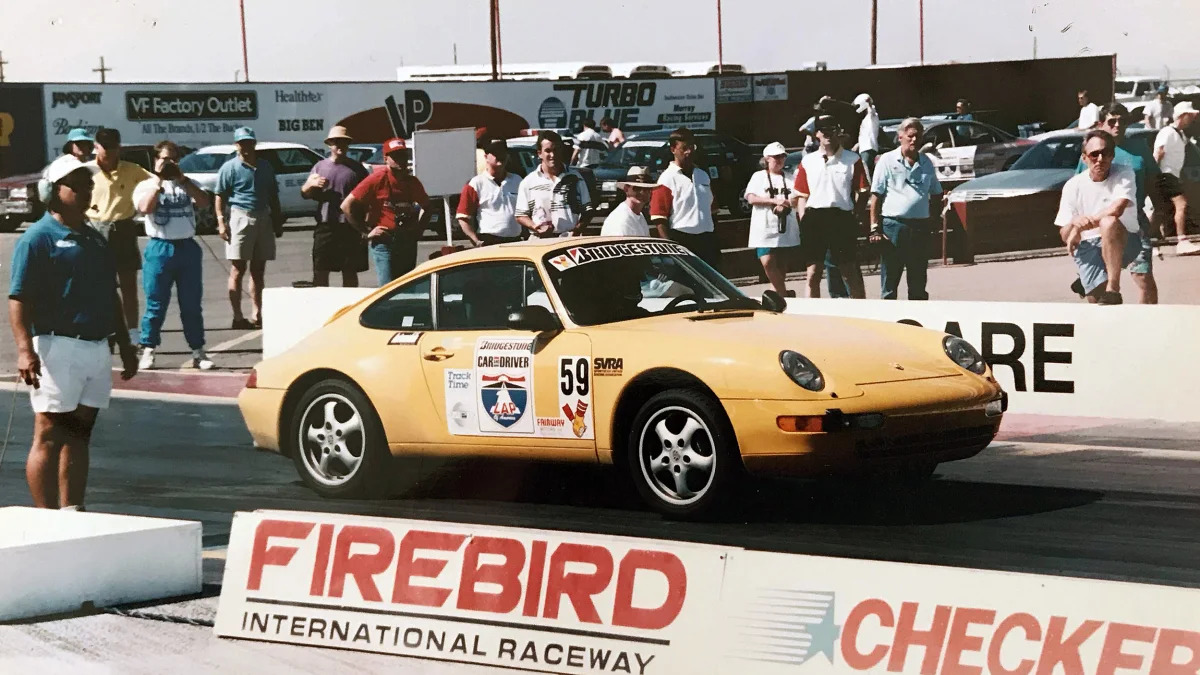

Vehicle: 1995 Porsche 911 Carrera Coupe

Team #59: Hurley Haywood, Jean Jennings

This was the year Brock refined One Lap from road trip to serious business. He cut about 3,800 miles off the map corners of the United States and made nine track events from Illinois to Arizona to Tennessee to Michigan the meat of the competition.

The first four cars that signed up were two factory 1995 Porsche 911 Carreras and two factory 1995 BMW M3s. There were plenty more Porsches, several Corvette ZR1s and all that jazz. It was game on from the start.

This circus still required one week to drive 5,200 miles while now fitting in racetracks. Time seemed tighter than ever, because each of the three-lap races involved paperwork, posturing, waiting, a familiarization lap, a hot lap and a cool-down lap.

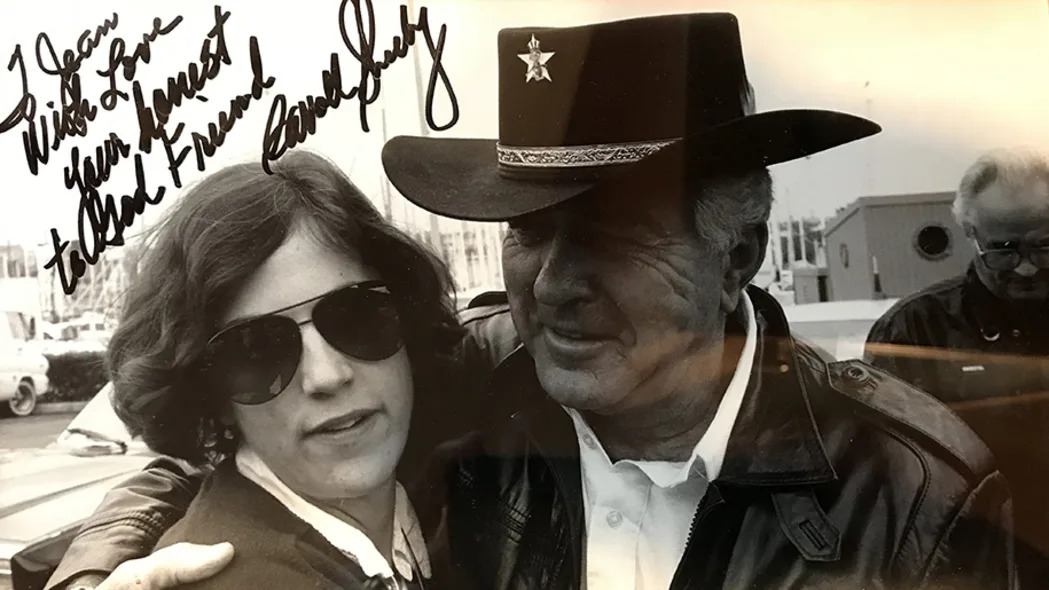

With the 911s, Porsche brought pro driver Price Cobb and the world's greatest endurance champion, Hurley Haywood. And Hurley brought me. We were friendly acquaintances, but we didn't really know each other. That would change.

In his mind, I was there to drive him around the country.

"When was the last time you drove across the country?" I asked.

"Never have," he said.

"Have you ever driven across Texas?"

"No."

"Have you ever driven anywhere but on a racetrack?"

"No."

In my mind, I was a good driver. That lasted until I stalled the 911 trying to throw money in a Chicago toll booth without stopping. There was a terrible choking sound coming from Hurley's side of the car.

"What?!?" I said testily.

"Who would have thought you couldn't drive?!!?"

Very nice.

With that opening, we settled in and became friends. I focused on getting us where we needed to be, he did the tracks. After the first "race" at Blackhawk Farms in Illinois, Hurley pulled off his helmet and said, "This is not my kind of driving." He felt much better when he found out he was three seconds faster than our teammate Price, who'd orchestrated side bets and now owed Hurley three bucks.

Hurley tried very hard to adapt, and his best runs were a third at Heartland Park in Topeka and a third at Second Creek Raceway in Denver, which he took in stride. As we left, he looked bemused. "I can't believe I'm in Denver and I didn't fly here!" he said. And Price still owed him $2.

Hurley was enthralled with America, with driving in Illinois through thunder and lightning he described as "like the Fourth of July!" I nicknamed him Toto somewhere in Kansas as we sped on below a tornado-black sky. My spirited all-night driving on twisty U.S. 550 from Montrose to Durango, Colo., roused him from a dead sleep. He pushed up his eyeshade without a word. "Would you like to drive?" I asked. "I believe I would," he said somberly.

By New Mexico, we were old hands at this One Lap. Still, turning onto U.S. 60 to face a vast nothingness gave both of us pause. "I've flown across big nothing places like this and stared down at the ribbon of road going across miles of nothing," Hurley said. "And I've thought, what poor asshole would be driving across this black strip to nowhere? Now I'm the poor asshole!"

I immediately suggested top-speed testing the 911 all the way home. He ripped off 172 before we hit the Datil Mountains, caught up with a Viper and slowed to 160 to pass. "Well that blew the snot out of his nose," Hurley chuckled.

In Oklahoma, we slept in the car until the track opened. Hurley was so tired, he hit the brakes at the start of the front straight when he saw the checkered flag. In Memphis, he spun in the midst of a blistering lap. And track officials had to bang on our windows in Indiana where we had parked in the middle of the night against the locked track gate. By then, it was so over. I took the wheel and drove us to Michigan while Hurley read the Star out loud.

Price Cobb and his journalist teammate Vince Bodiford finished first, and we managed a respectable fourth overall.

I took Hurley to the airport; he flew to Le Mans and won it.

We are still fast friends. Well, I used to be fast.

About Jean Jennings

Jean Jennings has been writing about cars for more than 30 years, after stints as a taxicab driver and as a mechanic in the Chrysler Proving Grounds Impact Lab. She was a staff writer at Car and Driver magazine, the first executive editor and former president and editor-in-chief of Automobile Magazine, the founder of the blog Jean Knows Cars and former automotive correspondent for Good Morning America. She has lifetime awards from both the Motor Press Guild and the New England Motor Press Association. Look for more of Jean's occasional Vile Gossip columns in the future.

Related Video:

Sign in to post

Please sign in to leave a comment.

Continue