With the NBA playoffs fast approaching, the Utah Jazz can boast the best record in the league. But the best team name? Not so much.

Some words just don’t work together. Comedian George Carlin called out “jumbo shrimp” and “military intelligence” in his bit about oxymorons. Utah Jazz works almost as badly.

“I’m sure that as players, we joked about it because there is no more unlikely city than Salt Lake to have a team called the Jazz,” said Rich Kelley, a 7-foot center out of Stanford, who played for the Jazz in New Orleans, where the team started, and in Salt Lake City. “There can’t be two more different cities in the U.S.,” he said.

The Jazz was an NBA expansion team born in the Big Easy in 1974.

“Jazz is one of those things for which New Orleans is nationally famous and locally proud,” then-co-owner Fred Rosenfeld said at the time. “It is a great art form which belongs to New Orleans and its rich history.”

Branford Marsalis, a pretty good saxophone player — three Grammys, 18 nominations, used to shoot some hoops, too. “I played, I didn’t play well,” the eldest son of New Orleans’ first family of jazz said the other day. “I was the guy that they put in when they needed five fouls.”

Marsalis, 60, was a teenager when the NBA arrived in his hometown. He and his three brothers had been exposed to the pro game with the ABA’s New Orleans Buccaneers.

“My dad would take us to those games regularly,” he said. “We had a great time.” But that team left town after three seasons.

The New Orleans Jazz lasted five years and headed West in 1979. Like Marsalis, they didn’t play well, never finishing above .500.

“They were playing in the Superdome, a place that holds 80,000,” said Marsalis. “You’d get 2,000, it feels like the loneliest place in town.”

“When they moved the Jazz to Utah and kept the name, we were like, ‘Man, these people are idiots,’ ” Marsalis said.

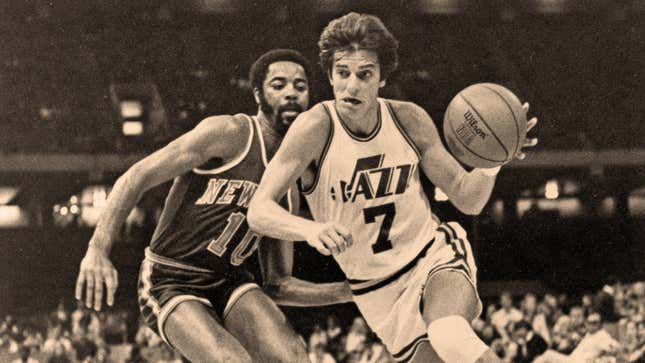

You could say that Utah led the league in turnovers that first year: Only three players on the New Orleans roster stayed with the team: Kelley, Pete Maravich and James Hardy.

“I think it was blasphemous to keep that name,” said Barry Mendelson, the executive vice president and onetime GM of New Orleans. Keeping the logo with a note for the ‘J’ irked him, too. “Jazz as an idiom is indigenous to New Orleans ... and so it makes no sense to travel anywhere else. So yeah, I was upset and concerned about it.”

Initially, the Utah team was going to be called the Saints (taking another New Orleans name, from the city’s NFL team), chosen in a contest by the local Chamber of Commerce in Salt Lake City.

Some of the rejected suggestions from fans included Salt Lake City Slickers, Salt Lake Salts, Utah Outlaws, Salt Lake Choir Boys and the 79ers, said Tim Grandi, the legal counsel for the team owners, laughing at the prospect of a 79ers-76ers matchup.

Grandi ran the names by Sam Battistone and his partner, Larry Hatfield. But Battistone decided to stick with the Jazz. The owner told Grandi, “When the Jazz do well, I want the league and the fans to remember that it’s the same team that was such an also-ran always in New Orleans.”

Mendelson has a different theory. “Sam had lost a lot of money on the team, and he didn’t want to spend another 10 grand on new uniforms.”

Battistone needed approval from the league and fellow owners to move his team. Part of that involved drumming up support in Utah.

Grandi recently looked through some boxes of his notes from that time. “The last handwritten note is ‘Sam to call Donnie and Marie.’” That was when the big Osmond brother-and-sister act had their popular TV show.

“We met them, they were real nice. And they were both such handsome people, and they were really interested in basketball.”

“They were about the biggest thing we had going,” said Ted Wilson, the mayor of Salt Lake City from 1976 to 1985. “Donnie and Marie were actually the biggest thing that ever happened to Utah for a while. We’re not really the fanciest thing around, you know. They sold us.”

Another Osmond, Donnie and Marie’s brother Merrill, wound up singing the National Anthem at the Jazz’s 1979 debut in Salt Lake City.

While residents and fans of the Big Easy are proud of their jazz traditions (trumpeter Al Hirt played at the team’s 1974 home opener, accompanied by fans with toy horns), Utahns make their own claims on the native American art form.

The former mayor, in a call from his hometown, admitted that “people kind of laughed and talked about the name around town. They’d say, the Jazz? Wait a minute, that’s New Orleans.”

But Wilson, 81, added, “There was actually a pretty strong jazz culture in those days. I played jazz trumpet in high school in Salt Lake City. And I used to go to jazz clubs when I was in college at the University of Utah. It wasn’t totally foreign to us.”

Even Marsalis, who performed the National Anthem at the NBA All-Star Game in New Orleans in 2008 and at the 1991 game with Bruce Hornsby, and has gotten used to the Utah Jazz.

“It was very strange the first couple of years. I used to laugh when I saw the Utah Jazz.” All these years later, when he thinks of the Jazz, those fine John Stockton-Karl Malone teams which fell to Michael Jordan’s Chicago Bulls in the NBA finals in 1997 and ’98, come to mind.

So, faced with a question of whether today’s New Orleans Pelicans might make a trade to bring back the Jazz name, Marsalis laughs. “Nah, the Utah Pelicans would be even dumber. They don’t have any pelicans there. They don’t have any jazz, either, but it’s kind of like it’s there now. It’s a part of the culture.”