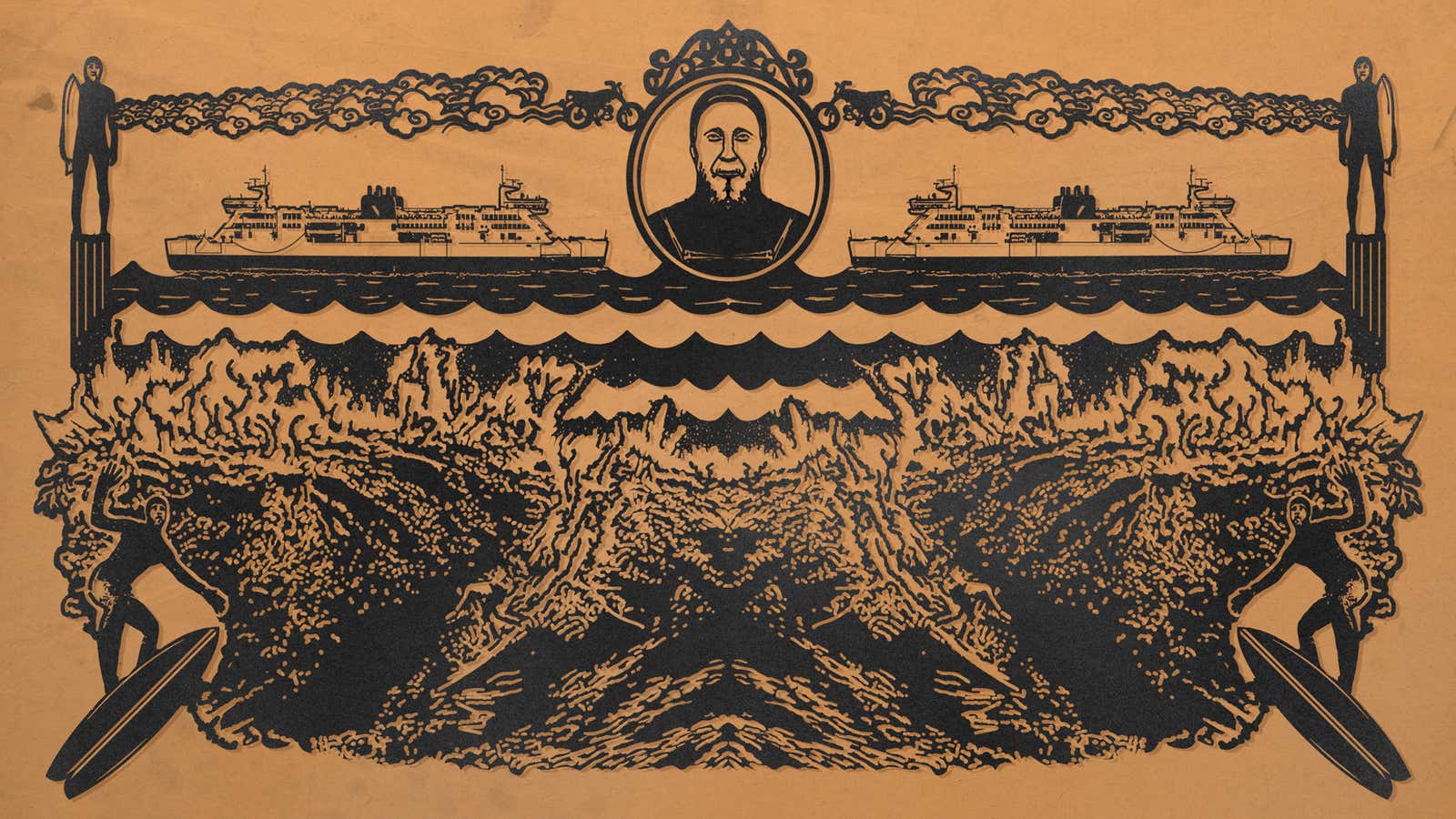

BERLIN — There’s this picture of Ira Mowen that pretty much sums up the quest he’s been on for seven years. In it, he’s standing mid-frame, gazing into the lens of the camera – or the phone, whatever. He looks like he’s just waking up, or he’s stoned, or he’s recovering from a sneeze, because he’s got that countenance that sometimes crosses the faces of people and makes them look, fleetingly, innocent; unencumbered by the machinations of adult minds.

Behind him, to the right in the picture, is a half-timbered house straight out of a Grimms’ Fairy Tale, and his rusty blond beard is encrusted with little icicles. He’s wearing what looks like a spandex bonnet; he’s an adult newborn swathed in neoprene. There’s snow on the cobblestone street. It’s hard to tell if he is holding a surfboard in the photo, but anyway, it would be weird if he were. This isn’t surfing country. This is Germany. Land of serious bread and even more serious notions of rectitude. Mountain land; land of lakes and rivers. Not of epic swells.

He might have been holding a surfboard, though. It’s actually not unlikely. Because Mowen is a surfer, and, even though it’s Germany, he found a wave. The picture is in fact a still from his movie about surfing in Germany, which, as a dude from California, he decided to do. It was back in 2011 that he first saw the wave. He had been living in Berlin for a few years, having chased a girl there and never left, when one night he overheard a few German friends of his talking about surfing, and the next morning they all drove out to some bizarre breaks on the Baltic Sea coast.

The Baltic Sea on its own isn’t generally big enough to develop the turbulence far from shore that, over hundreds of miles, organizes itself into serried sets of waves. But every day, at two-hour intervals, an enormous ferry cruised over from Denmark, and the breaks they were checking out were created in the ship’s wake. Mowen later went back to a couple of nearby spots and thought the waves looked rideable. He decided to try.

So that was his quest. Ride the wave created by a passing ship. He wanted to document it, too. At first, he just wanted to create a sick little film to post on the internet, just a couple of minutes of him ripping a wild wave. But the wave turned out to be a capricious despot. It took over Mowen’s life. It lured him into the water again and again, and then it ran away like a startled rabbit. One time it was in one place, and the next time it came, it was somewhere else. Sometimes it was good, sometimes it was bad. More than anything else, Mowen just wanted to paddle into the thick muscle of its velocity. He wanted a temporary enlightenment, a moment of reprieve in consonance with the water. But the wave would not be won.

Mowen travelled to the wave on a weekly basis, taking the train or riding his moped the three hours from Berlin. He took friends with him who could help film from shore, and when he ran out of favors to cash in and his friends ran out of patience, he recruited his mom and trained her to work the camera.

He was on a hard deadline, because the company that owned the ferry line was planning on upgrading its fleet. It wasn’t at all clear whether the new ships would create the wave. Mowen found his wave in November 2011 and the upgrade was supposed to happen in March of the next year. That meant he only had a few months to ride it, and film it. Those months also happened to be the most bitter of northern Germany’s twilight season, when the light hardly ever evinces day and the wind acts like it’s got a score to settle.

Every time Mowen pulled on his wetsuit and waded into the Baltic Sea littoral, when he paddled past floating chunks of ice or jumped off the jetty, he made sure someone was filming. He was possessed by the wave, but soon it became something else too. Mowen’s quest to surf the wave became synonymous with his desire to record the process. He launched a website for a documentary film project he called Surf Berlin. To raise funds for production, he started a crowdfunding campaign. “After seeing this wave, I was just totally fascinated by it,” he said in the Kickstarter project’s introduction video. “I couldn’t find that anyone had surfed this head-high barreling wave and then while researching it I found out that this wave was endangered and would soon become extinct.” Mowen said that he couldn’t stand the thought of letting such a strange and bewitching wave disappear without ever having been documented.

It was a beautiful project. Mowen posted photographs of his spot where things seemed out of proportion: pewter sky towering over a tempestuous sea; enormous ship blotting out the horizon over sapphire waters. He quoted Ralph Waldo Emerson (“The health of the eye seems to demand a horizon.”) The wave looked like a pristine little barrel; a right breaking cleanly for almost a full minute. Mowen’s documentary was written up by Surfer and Outside magazines; he was interviewed by Gizmodo and Vice. It was like a dream: a perfect, undiscovered wave that would be surfed only by one fanatical madman before disappearing forever. It was also like a dream in that it would prove only a dim shadow of what was true.

The location of Mowen’s wave was a little seaside resort town named Warnemünde, which derives from Warnowmündung that translates literally to “mouth of the Warnow,” because it is where that river flows into the Baltic Sea. Warnemünde is a popular cruise ship stop, and is considered almost an extension of the city of Rostock, once a prominent member of the powerful maritime Hanseatic League and still an important port. In the middle of Warnemünde, on a street that runs adjacent to the town’s central park and that ends at the seaside promenade, is a surf shop owned by a thirty-something local named Hannes Winter.

Winter, along with another surf shop owner named Joscha Jancke, was among the first German surfers to take note of Mowen’s quest in the waters just beyond his store. It annoyed him. “He sold himself as the discoverer of this wave,” Winter told me. “But he had come into the shop and asked about how to surf it.”

Warnemünde, occupying the western side of the Warnow estuarine channel, protrudes from an otherwise concave northern shoreline. At the town, the coast forms a kind of lopsided half-moon, and the ferries, entering the channel on their way to Rostock, created wake waves at two spots: near a point of the crescent, where the breakwater juts out into the sea, and closer to its nadir, off the beachfront. Mowen’s wave was off the breakwater, closer to where the ships entered the adjacent harbor.

Of the two spots, the waves were more reliable nearer the beach. When the wave appeared off the jetty, and whether it was rideable, seemed to be a function of multiple variables. The weather mattered, as did the direction of the wind and the water level, but even more important was the speed of the ship and the weight of its cargo. On the occasions that the conditions cooperated, and the wave near the jetty appeared, it would be larger and more powerful than the beach wave. Winter estimated that when the surf stars aligned, every other ferry passage would produce a jetty wave. It would break slowly, offering a long ride that occasionally had enough brawn to support a short board. But because there were so many factors that lent themselves to the wave’s creation, it was fickle. “You could never say, okay, that’s where the wave is coming,” Winter told me.

To Winter and his fellow surfers, that was no deterrent. They studied the wave and examined the ships’ speeds and courses on live tracking apps, and though they surfed the beach break more often than the one out near the jetty, Winter told me they caught rides at both spots. Videos online show a dozen surfers lined up at the beach break, pumping the shit out of some mush. A short documentary filmed in 2011 by Christoph Leib has a couple of riders catching some sweet little barrels, just a couple of feet high, and keeping the lip at their heels. It’s not the most graceful surfing you could ever witness, but these guys work their way into the wave like they’re easing into an old baseball mitt.

So in 2014, when Mowen started the fundraising campaign for his film, the tiny surf community in northern Germany went ballistic. How could Mowen claim to “discover” a wave that was already being surfed, how could he call it Surf Berlin, how could he claim that he was the only person riding the wave? Berlin was 250 kilometers away, and it was a different world. Where the untethered global cool kids haunted Berlin, Rostock and its adjacent were redolent of old-world maritime lucre and salt-stained seafarers. “From the distance it looked a bit like a guy from America comes to Berlin to do art or for partying and is absolutely surprised that there is an ocean at all,” Jens Steffenhagen told me.

Steffenhagen is the editor of Blue, a German surf magazine, and he was not impressed by Mowen. “I mean, the cliché is that North Americans are not very good at geography. So maybe he’s surprised that there is an ocean—and then he is super surprised that there is a wave, and he thinks that it’s such a sensation that he has to tell the world about it.”

Steffenhagen told me the impression Mowen gave upset a lot of surfers. “It was a bit ignorant to local culture,” he said. Aside from the wake wave, there are breaks all along the northern shore and off the German North Sea island of Sylt that are surfed, though in both cases they are usually crumbly in a way that the wake barrel wasn’t. Shortly after Mowen started his fundraising campaign, Steffenhagen wrote an article chronicling what he perceived to be an enormous swindle. He talked to half a dozen surfers who methodically dismissed Mowen’s claims. (An excerpt: “Ira’s claim #2: The ferry wave at the entrance to the harbour has not been documented before Ira started his film project; Vytas Huth, local: “A lie. Although there is not much material to be found online, it has been documented.”)

It’s hard to tell exactly what bothered Steffenhagen the most about the whole thing. On the one hand, he said it wasn’t just about Mowen’s abuse of facts. About being the first guy on the wave, for example. But on the other hand, he talked at length about a famous case in Germany of an illustrator who forged diaries and claimed they were the secret trove of Adolf Hitler. (One of the country’s leading magazines bought the forged journals for millions before the deceit was uncovered.) The truth is something to be taken seriously, he implied. So, was this a controversy over what was objectively true about the wave, or was it more a sense that someone—an outsider, no less—was unfairly occupying the narrative? “This whole story,” Winter told me, “it’s just a bit fake.” That last word, he said in English.

A few minutes after I met up with Mowen in Berlin, he proposed that we smoke some weed. I was asking a lot of questions, he said, and, honestly, it was a bit much. He was impressed I had gotten in touch with him at all, really. He doesn’t like being online. He usually doesn’t answer emails and things like that. It was good that I called, actually. That’s the best way of getting a hold of him (he hadn’t given me his number, but that’s another story). When I first called, it was almost noon on a dismal, rainy day and Mowen answered in a voice that seemed caught mid-yawn and told me somnolently that he was going on a hike. Pause. Would I like to come? I said yes.

To be honest, I thought he was joking. But I found Mowen, now 36, sitting on a chair in a warehouse in the always-almost-hip Berlin neighborhood of Wedding, tying up a pair of hiking boots. He was tall and blond and so pale that he looked devoid of color, and his raincoat reflected the light like a silvery beacon. When I asked where we were hiking to, he said we were going to Potsdamer Platz, a gaudy plaza smack in the middle of the city, five kilometers south.

For a second, I wondered why he used the word hiking when we were just walking through the city, but then we traversed spindly little paths through parks and gave sidewalks the widest possible berth and I thought maybe I was being an annoying pedant and went with it. Mowen told me that he was a terrible surfer; that he once surfed Ocean Beach in San Francisco while he was in the city studying art, and it had been so big that it took him half an hour just to paddle out. He had taken the wrong board, and it was one of those days where every wave looks like a boiling concrete wall, and he barely made it out of there in one piece. That’s is the kind of surfing he doesn’t really see the point in. The danger isn’t appealing. “I don’t really care about how I surf,” he told me. “I just like the ride, you know.”

We walked down to the Berlin Philharmonic and listened to a free concert, and then snuck into a nearby film institute to try to filch a lunch at subsidized student prices (the French woman running the cafeteria wasn’t having it). I asked Mowen what he thought about the negative reaction from German surfers. He told me maybe he hadn’t been totally honest, in the beginning, about what the project was about. The real quest said, he said, wasn’t about being the first to discover the wave or being the first one on it. No, the real journey was the one he went on. It was about that time in his life, a dark time beset with disease and poverty. The story was about him deciding, at one of his lowest points, to turn himself over to obsession and let it inhabit him.

That’s the thing about Mowen. He does want to tell the truth. Maybe he is more interested in the truth than anybody. He’s just not talking about some objective truth that will check out for everyone. His truth is an individual thing, it’s an artist’s truth. In Mowen’s own, self-generated story—the one that he filmed and curated, performed and edited—the meaning of his personal experience is much more important than the details of history, context or society. Facts are sublimated to story. It’s not even solipsism; it’s a preference for self-regard in service of the aesthetic.

“There’s this principle in physics, what’s it called? It’s famous. Like, the Eisenberg principle,” Mowen was sitting across from me in the cafeteria on the 11th floor, thinking about the truth. “It’s like, you can never experience a situation truly, even in real life, because even the fact that you’re there is changing it.”

I looked that one up on my phone. “The Heisenberg Principle,” I read out loud. “The position and the velocity of an object cannot both be measured exactly, at the same time.” It’s also called the uncertainty principle.

Later on, I looked it up again, and realized that he probably meant the observer effect, since the uncertainty principle describes the impossibility of precisely measuring two things at once rather than the impact of observing them. At first, I had assumed he was talking about the wave itself. It made me think about that Aldo Leopold story where he watches a wolf die, about the sense of powerlessness in the face of a furious sea, about the new lifeguards at Nazaré, and about the compulsion possessed by anyone who has ever surfed to check the waves at each strange shore and imagine what it would be like to ride them. Because to surf is to try and commune with a force of nature.

But Mowen wasn’t talking about that at all. “A story can never be told in its truest sense, basically, is what that means,” Mowen said. He was talking about how the best takes of his movie are the ones filmed when he forgot the camera was on.

When I was a kid, one of my uncles used to take me out to eat, and when I got to pick the restaurant, I pretty consistently chose Islands, a California burger chain featuring a hokey Hawaiian theme. On televisions around the restaurant would play endless loops of surfing videos; guys (almost always guys) whipping across jagged blue cliffs or bowing through a turquoise tunnel like they were saying a prayer. Those surfers were pretty much at the top of their game. They didn’t need an adjacent plot; no explanation was necessary for what they were doing because it spoke for itself. Their sea-sprayed arabesques were a wonder to behold whether you surfed or not. Theirs were feats of ecstatic athleticism, and the product of prodigious effort. It was pure ability, without need for narrative. I loved watching them, even though their highlight maneuvers seemed far removed from the mostly solitary reverie of waiting for a wave—that watchful trance that makes up so much of surfing.

In a sense, Mowen’s project is the inverse of that. One man, trying to overcome a hellish hurdle: It’s a saga that works at any level of ability, maybe it’s even more poignant by virtue of its protagonist being someone with so little claim to anything like greatness. This is not what people have a problem with, though. “We all want him to finish the film,” said Steffenhagen, the editor of Blue. “We just didn’t want him to make money with false claims with regards to discovering something that was already discovered.”

So is Mowen a fraud? His first fundraising campaign failed well short of its funding goal of $40,000. A second campaign, launched two years later with a lower goal of 8,761 euros (nearly $10K) and an extended disclaimer about his being introduced to the wave by German surfers, succeeded. I can’t claim to know exactly what was going through Mowen’s head the first time, but he told me he was operating by the California ethos of protecting a good spot. He also said his project was, from its inception, misunderstood. The second campaign shows evidence of his efforts to be clear about what his project was; it included, among other changes, a slightly altered title: Surf Berlin – A Spiritual Quest. Anyway, he might have just thought that telling a story about one man trying to ride one wave almost 150 times, and failing nearly as often, simply wouldn’t be enough.

A couple of years ago, Mowen had a nightmare. He was paddling out. This was the break he grew up surfing, near Santa Cruz, and he recognized it. There were the cliffs. There the coastline jutted out. Around him, surfers were bobbing on the water. They were waiting for a wave, just like he was, but there were no waves coming. The water was as stll as flint. Suddenly, in the distance, looming out of the water like a menhir bisecting the horizon, came the ferry ship. All at once, the surfers started thrashing through the water, in a mad dash to put themselves in the right position for the wave that would appear without foretelling where. The wave haunted him.

Back in 2012, after his deadline for surfing the wave had passed, and Mowen had only filmed himself riding one unsatisfying little barrel, he headed back to Santa Cruz for his father’s birthday. He brought his board with him, and surfed his home breaks almost every day for nearly two months. The project was ostensibly finished, since he had done what he set out to do. But he wasn’t happy. He also knew the ferry ship company was still operating at least one of the old boats, since their upgrade to the new fleet was behind schedule. When he got back to Berlin, he decided to go out one more time.

This last part, Mowen told me maybe I shouldn’t mention. It could give away the end of the movie, and that would be a shame. I thought I should tell you anyway, though. The boat fleet was finally upgraded, and so maybe no one ever will surf that exact wave again, even though the new ferries still produce a break off the jetty ever now and then. Mowen is still working on his film, although he is more vested in another, new project and he doesn’t know when Surf Berlin will be released. But he did finish the first part of his quest. One sunny morning in June, Mowen surfed the wave, and it was exactly the wave he had been waiting for. On that day, at the start of summer, after chasing it for months, Mowen told me he experienced a moment of pure bliss. Of communion.

Jessica Camille Aguirre (@jessicacaguirre) is a freelance journalist currently based in Germany.