The End of the Domestic Flex

Latest

There’s a domestic revival brewing—or at least, a hot Instagram-driven market demographic. Alison Roman, the millennial Rachael Ray, moved a generation to take to their kitchens in droves; cookware startups like Potluck and Great Jones have capitalized on this impulse by creating affordable options for those looking to take up cooking as a hobby, operating under the shared assumption that the best way to get millennials (as well as those slightly older and slightly younger) to do anything is to present them with an opportunity to flex online. But now, our collective turn inward is in fact mandated; authorities have instructed huge swaths of America to stay inside as much as possible to stop the spread of coronavirus. Now, we will have to stop caring about what the slop we make looks like and focus instead on the simple act of feeding ourselves.

In November 2019, a former food writer named Sierra Tishgart launched Great Jones, a cookware startup that sells basic pots and pans in trendy colors, targeting young urban millennials interested in getting really into soup. The company’s wares aren’t dissimilar from other offerings already on the market and differ from their aesthetic ancestors, Le Creuset and Staub, primarily in price. Great Jones’s The Dutchess—their version of a dutch oven—boasts shiny handles and looks like it would photograph beautifully on a table strewn with wildflowers, random sheaves of wheat, and a long linen runner. For people new to cooking and invested in the idea of documenting their hard work for an audience, Great Jones is the answer: functional and cute cookware that doesn’t have to live under the sink in a jumble of Tupperware lids.

Writing in Bon Appetit around the time of the brand’s launch, Tishgart said that her goal for Great Jones was to simplify the process of learning how to cook, by cutting through the noise of the various pots and pans already available on the market. “The choices were overwhelming,” she wrote. “Why did one brand sell dozens of ‘different’ stock pots? Carbon steel or cast-iron? The ‘perfect’ collection would include 20 different pieces and cost well over $1,000. Why did this feel so complicated?” The answer to her invented dilemma was a range of kitchen basics that includes practical items like a saucier pan and a non-stick skillet, as well as a Dutch oven and a giant stockpot. All the cookware comes in Instagram-friendly colors like “broccoli,” a muted deep green, and “mustard,” a brighter play on the jaundiced millennial version of the shade. It serves, as writer Amanda Mull noted at The Atlantic, as a new trophy for millennials turning inwards towards domesticity for clout.

Domesticity is an unsurprising reaction to aging, but the status anxiety that created FOMO is now redirected towards products. Anyone can make a pot roast, but if that pot roast isn’t on Instagram, glistening in the warm embrace of a Le Creuset dutch oven, does it really count? Mull’s argument is simple: we are moving towards domesticity and its photogenic accessories as a new way of communicating status. (Or at least, a way that has resurged in popularity.)

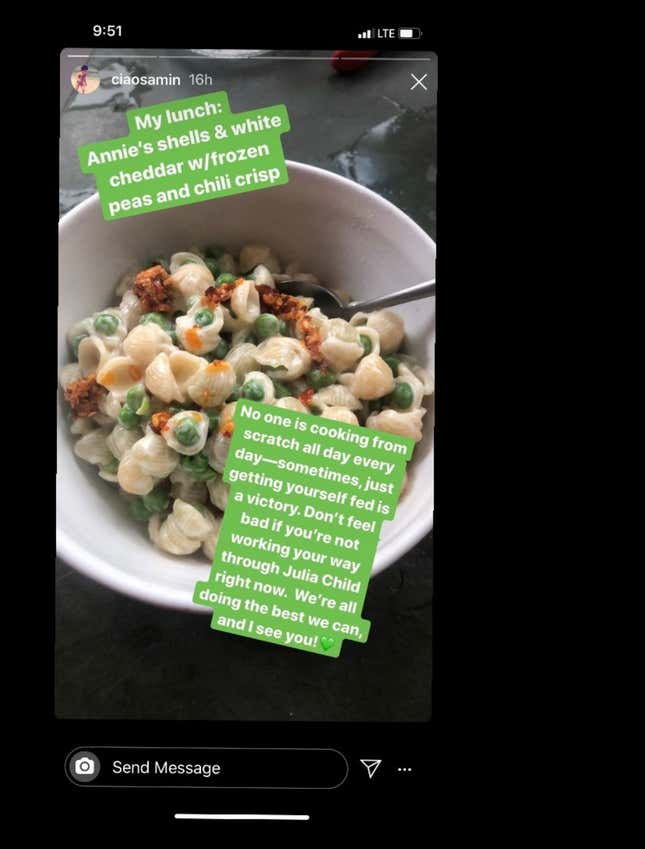

Cooking for Instagram, whether with Great Jones’s cookware or a battered Ikea stockpot, is by definition a social activity. Roast the big chicken for friends, serve it on a hand-thrown ceramic platter and take a picture quickly, before the perfect image—the food you’re about to eat—is ruined. Making the dish is one thing, but making sure the dish looks good and meets the approval of others is a second, unspoken rule that drives the urge to share. But now, when social distancing is a necessity and cooking is no longer a quirky affectation but something we all have to do not as a hobby but for sustenance, it no longer matters if the food we make looks good, as long as it tastes okay and does its job, which is to feed a hungry body.

There’s a line of thinking that this pandemic is an opportunity to use the newfound hours of downtime to optimize, to self-improve, and to emerge from these strange times with 10 new skills, a book proposal, and the ability to make a baked Alaska from scratch. A tweet that went viral recently reminded everyone that Shakespeare wrote King Lear while in quarantine from the plague. Hello! published a list of activities to do while stuck in the home, including scrapbooking and learning how to knit. Self-imposed productivity in times of existential distress is one way to distract from the question of whether your town has enough ventilators for what’s coming, and it’s unsurprising that stress would flood into a channel that already exists, i.e., performing highly photogenic domesticity. But cooking ever-more complicated meals for clout or for personal pleasure and then failing at those attempts will likely create more stress—an ouroboros of anxiety from which there is little escape. Spending weeks stuck at home, staring at the walls, contemplating what it was like before, will only intensify the spiral.

What the great domesticity revival misses, though, is the fact that people have been cooking, canning, baking, and just making food to survive for a very long time, with or without the use of expensive and pretty kitchen tools. A lasagna baked in a clear, serviceable Pyrex baking dish will still be delicious, even if Pyrex doesn’t photograph nearly as well as French ceramic. (Though of course at one time it was Pyrex that was the new, pretty, affordable way to brighten your kitchen.) But there’s no choice, anyway: whatever stockpot or casserole dish you have on hand will have to work for now, until the poison rains clear and we are once again free to go to a store for new equipment and fresh flowers for guests without a care. Documenting every meal, as a means of journaling or otherwise taking note of these remarkable times, is one thing, but exerting additional pressure on yourself with an eye towards great ambitions is a fool’s errand.

But even the strongest will eventually fall prey to vanity, or just the desire for an acknowledgment of their existence from someone other than themselves. Over the first weekend of real, sustained social distancing, my Instagram feed turned into a low-fi cooking blog, full of pictures of soup and stock. On Sunday, moved by nothing more than boredom and an idle restlessness, I made a lemon cake. It is middling but passable and photographs, I’m sorry to say, pretty well. I sent the picture of the finished result to a friend and felt a small pang of satisfaction when he replied.