Like most Oilers—or “Earlers,” as they were known as their star galloped his way to Rookie of the Year and two MVP trophies his first couple of years in the league—Earl Campbell loved playing for the cowboy-hatted, easy-going Bum Phillips, who was always easy with a wisecrack. Bum once said of the team’s reliable place-kicker Toni Fritsch, an Austrian: “I’ll tell you one thing, every time I see that kid going onto the field, I thank God for our country’s immigration laws.” And he once updated reporters on Campbell’s injury status this way: “Earl’s walking better, but he’s much more valuable to this team if he can run.”

That joke got at a complicated truth about their relationship. On the one hand, Bum appeared to be another in a line of father figures to Earl, whose own dad died when he was 11 years old. Coach Darrell Royal had fulfilled the role at the University of Texas—Earl, in a 2012 eulogy for Royal, said “I’m one of the only players who really got close to him”—and now, Phillips, a warm man widely beloved by his players, took the mantle.

“You deal with a player the way you want him to deal with you,” said Phillips, who brought beer kegs to the training field on Thursdays and on Saturdays encouraged his players to bring their wives, kids and dogs to practice. “You can’t expect loyalty if you’re not loyal.”

With their rural Texas backgrounds and love of country music, Phillips and Campbell had a deep affinity for each other, and when Phillips was fired by the Oilers in the early 1980s and rehired by the New Orleans Saints, Earl followed him to Louisiana to finish out his career.

On the other hand, you could say that Bum Phillips took advantage of Earl, running him ragged in a way that made Campbell appear both heroic and tragic. Campbell wanted to impress men like Royal and Phillips. He had a kind of desperation to please, one that translated into success on the field. “I always thought if I let one or two guys tackle me, I wasn’t doing something right. I wanted a bunch of them to get me.”

That sort of mentality served Earl Campbell brilliantly on the gridiron. He won a Texas high school football championship in 1973. In 1977, at the University of Texas, he won the Heisman Trophy, given to the best collegiate player, carrying his team to the brink of a national championship. He was a star for the NFL’s upstart Houston Oilers, the anti–Dallas Cowboys, lifting an otherwise workaday pro football team to greatness. Opponents dreaded having to tackle him: “Every time you hit him,” the linebacker Pete Wysocki once observed, “you lower your own I.Q.”

Perhaps this is the exploitation fixed into the game of football: Bum Phillips, whose trademark was treating his players like adults, who shared genuine kinship with them, surely didn’t wish any of them harm. But the game itself, in all its brutality, locks everyone within its orbit—from coaches to fans—in a kind of complicity as the players battle on the field for victory.

As early as October 1979—when Campbell was merely 24 years old, a second-year pro—the daily newspaper in Austin, the American-Statesman, ran a story titled “Campbell’s Style May Take Its Toll.” Speaking about Campbell’s no-out-of-bounds running style, his habit of running over people instead of around them, Franco Harris, the Steelers running back, observed: “Knocking over people can look very good but you can’t do it forever. Sometimes it’s got to catch up with you. Sometimes it’s going to be somebody else who knocks you over…so the most important thing I think isn’t to get a few extra yards every time but to make sure you’re healthy enough to play.” And the Cowboys’ star running back, Tony Dorsett, shuddered when asked about Campbell’s methods: “If I ran that way, I’d get chopped in half. When you’re dishing out the punishment like he does, you’re taking a lot, too. I hope to get together with him this spring. I might tell him jokingly, ‘Hey, man, why don’t you let just one tackle bring you down sometimes?’”

Campbell has long been defiant—even defensive—when it came to questions about whether his running style was bad for him in the long term. “This perception of abuse on my running abilities is definitely wrong,” Campbell said when he was still a player. “In fact, I want the ball 30 times a game. I’d be upset if it didn’t turn out that way.” He had a favorite phrase during those playing days, as if he had studied the physics of football: “It’s the hitter versus the hittee. The hittee gets hurt worst.”

Campbell sums up his career this way: “I truly believed I was invincible on the football field.” He convinced himself that a third-and-3 was actually third-and-6 so that he would run with an anxious abandon to get that first down. And so the strategy for his coaches became plain: pound Earl. “To appreciate Campbell,” Bum Phillips explained in the fall of 1978, Campbell’s rookie year as a pro, “you’ve got to give him the ball 20, 25 times a game. He’s the kind of guy who doesn’t let up. He’ll turn a four-yard run into a 12, or a one-yarder into a four, which is a heck of an accomplishment in this league. I think most of his yardage in college was made after he got hit. Most backs, you block two yards for them and that’s what they’ll make. But you block two yards for Earl and he’ll get four. Do that three times and you’ve got a first down.”

Bum meant this admiringly, of course. But look at Earl Campbell now, who often moves around with a walker, and those are wince-worthy words. Sometimes, he has said about the simple act of walking, “it seems like something in my body won’t let me put my left leg up to the right one and just keep going.” And he has admitted to what he calls “short-term problems” related to memory.

Reporters asked Bum Phillips about leaning so heavily on Campbell, especially late in a game in which the result was no longer in doubt. “Many of y’all have questioned my use of Earl Campbell, since it’s obvious that it takes him longer than most players to get up off the ground,” Bum Phillips said about his charge. “That’s true. But did y’all ever notice that it also takes a long time for Earl to go down on the ground?” It was the sort of line that endeared Bum to the press, to the fans, and to his players. “He’s the kind of guy you’ve got to give the ball to lots of times—25 to 30 times a game—no matter what he’s doing,” the coach said. “He wears a team down. Eventually he’s going to break one. You can feel it, like a time bomb ticking. He keeps rocking, rocking, and all of a sudden, he’s gone.”

“Earl Campbell is the best running back who ever put on a pair of shoulder pads,” he crowed about his star player. “He always got better from his 20th carry to his 35th, ’cause by then he’d done hammered ’em way down.”

The hammering went both ways. Years later, after Campbell got both knees replaced in his 50s, after he began undergoing nerve therapy to combat the effects of a neurological disorder called chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy, which can lead to declining strength and sensitivity in the arms and legs—even after all this, Bum Phillips, who died in 2013, told an interviewer: “I never felt like he carried the ball too much, and he didn’t either: He hurt people, he didn’t get hurt.”

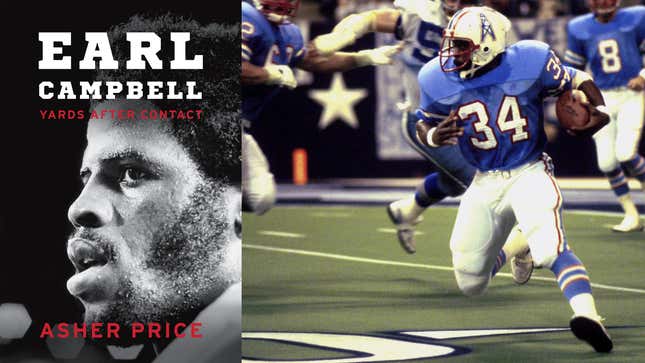

This adapted excerpt from Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact is published with the permission of University of Texas Press.

Asher Price is a staff reporter for the Austin American-Statesman and a journalism fellow at the University of Texas Energy Institute.