The following is an excerpt from The Bastard Brigade: The True Story of the Renegade Scientists and Spies Who Sabotaged the Nazi Atomic Bomb, by Sam Kean. The book is out today and can be purchased here.

In 1944 the long-discussed plan to kidnap Werner Heisenberg suddenly gained momentum and took off at a gallop. Heisenberg was already a legendary physicist then (the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle is named after him), as well as an ardent German patriot. He was also the leader of Nazi Germany’s dreaded Uranium Club—their version of the Manhattan Project to build an atomic bomb.

Allied spies had finally traced the physicist to Germany’s Black Forest, a name right out of Grimm’s, and with their top scientific target in sight, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)—the precursor to today’s CIA—began plotting to lay hands on him.

The soldier they chose to lead the mission was Carl Eifler, once described as “without a doubt the toughest, deadliest hombre in the whole OSS menagerie.” Eifler, who’d joined the army at age 15, was a pugnacious and unscrupulous soldier. “Consider yourself a criminal,” he once advised OSS recruits. “Break every law that was ever made.” He stood well over six feet tall and weighed 280 pounds, and his size and demeanor regularly drew comparisons to a grizzly bear. His hobbies included shooting shot glasses off the tops of people’s heads while drunk.

Eifler made his reputation in 1943 while battling the Japanese in the jungles of Burma. Despite starting with just a few dozen soldiers (including film director John Ford, who recorded several live ambushes), Eifler soon commanded an army of 10,000 angry Burmese natives, and dollar for dollar he ran one of the most successful campaigns of the war. Using hit-and-run tactics, the Burmese irregulars destroyed dozens of airfields and railroad stations across 10,000 square miles of jungle; they also killed and wounded 15,000 Japanese troops, compared to 85 deaths on the Burmese/American side. (One favorite trick involved planting bamboo spikes in the weeds alongside a road and ambushing Japanese soldiers, who impaled themselves when they dove for cover.) Many Burmese natives kept shriveled brown ears from Japanese corpses as souvenirs, which they carried in bamboo tubes slung around their necks. Some had several dozen.

In his most famous exploit, Eifler and a few men set out to raid a Japanese base along the Burma coast one day in March 1943. But choppy seas prevented their boats from landing, and they risked being dashed on nearby rocks or swept out to sea. Just before they lost control, Eifler grabbed a towline, leapt into the water, and started thrashing for shore. The chop slammed his head against the rocks several times, and the undertow almost dragged him down for good, but several minutes later he managed to stagger ashore, bloody and woozy. He then used the towline to drag all five boats to safety before passing out.

Although he saved the mission, Eifler woke up with ringing in his ears and an excruciating headache. (In smashing against the rocks, he’d probably suffered several concussions, if not outright brain damage. He would later experience seizures and other neurological problems.) Over the next few weeks his thinking grew foggy, and he had so much trouble getting to sleep that he had to scarf painkillers and gulp bourbon each night in order to black out. This didn’t exactly improve his mental state, and he sometimes burst out crying for no reason. Rumors of his erratic behavior finally reached the head of OSS, “Wild” Bill Donovan, who had little choice but strip him of his command, a humiliating development.

The demotion pained Donovan, too: as a fellow reckless warrior, he sympathized with Eifler’s plight. Moreover, Eifler was too valuable an asset to let sit idle. So at some point over the next few months Donovan mentioned another adventure that he thought might appeal to the deadly hombre—a little lark to hunt down a certain scientist in Germany.

After some much-needed rest, Eifler began meeting with OSS officials in early 1944 to discuss the mission, which was so secret it never received a code name. Accounts of the meetings differ, but Eifler first sat down with one of the deputies of Gen. Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, who briefed him on Heisenberg and nuclear bombs. Eifler had no idea what “fission” meant and even less of a clue who Heisenberg was, but he understood dirty warfare. He finally interrupted, “So you want me to bump him off?”

Groves’s man winced. “By no means.” Instead Eifler should “deny the enemy his brain,” the euphemism they’d settled on for abduction. “Do you think you can kidnap this man and bring him to us?”

Eifler didn’t hesitate. “When do I start?”

“My God,” Groves’s man marveled, “we finally got someone to say yes.”

A few days later Eifler met with Donovan and other officials. By this time he’d conjured up a cover story, a tale meant to fool the Allies as much as the Germans. He planned to launch the mission from Switzerland. He’d pose as an American customs agent there, claiming that he wanted to study how neutral countries handled border control during wartime. “This gives me the opportunity to observe their borders,” he explained, “and figure out how to violate them.” For the actual kidnapping, he suggested using a dozen commandos to raid Heisenberg’s new lab, located just fifty miles from the Swiss border. After bludgeoning the physicist into submission, they’d smuggle him back to Switzerland, steal a plane, and fly to England. No sweat.

Donovan immediately objected—not to the manhandling of Heisenberg or the gross violation of Swiss neutrality, but to landing in England. Under no circumstances did they want the bloody British involved. Eifler accepted this limitation. He then began thinking out loud and came up with an even wackier scheme. Instead of steering the stolen plane for England, they could fly toward the Mediterranean. Then maybe they could ditch the plane over the water and parachute into the freezing sea. Oh, and then rendezvous with a submarine in the darkness, which would whisk them through the phalanx of U-boats there to safety.

Lacking any limeys, this plan suited Donovan just fine. Ironically, it was Eifler who started thinking it through more, and pointed out some potential difficulties. What if the submarine got delayed? Or what if storms prevented the rendezvous? Donovan merely chuckled. Carl Eifler, he said, you’re the last man on earth to be worrying about undue risks. That was probably true, Eifler conceded. But he did have one more question: What if we get caught?

The answer sounded familiar: “Deny Germany the use of his brain.” But the meaning of the euphemism had suddenly grown darker. Eifler now had permission to shoot Heisenberg rather than risk him falling back into German hands.

Eifler nodded. “So I bump him off and get arrested for murder. Now what?”

“We deny you.” Deny they’d ever heard of him.

Okey-doke, said Eifler. It was the answer he’d expected, and it didn’t trouble him. Time to get to work.

For once, though, OSS had second thoughts about a nutty scheme. Donovan admired Eifler’s gifts, such as they were, but the man was simply too gung-ho for a mission like this. Germany wasn’t a jungle where you could butcher your way out of a tight spot. Kidnapping Heisenberg would require tact and subtlety—less smash and more dash. So in the summer of 1944 Donovan once again had to yank command from his top warrior, and this second demotion proved even more gut-wrenching than the first. For privacy, they met on the balcony of OSS headquarters in Algiers, where Eifler was training. Donovan gave some bullshit excuse about how the Manhattan Project had “cracked the atom,” which supposedly rendered the kidnapping moot. Still unclear about the physics, all Eifler understood was that he’d been relieved of command again. He managed to keep himself together in front of Donovan, but a few days later, during a conversation with a friend, he lost it. The embarrassment, the stress, the continuing mental turmoil from his injuries in Burma—it proved too much, and he broke down sobbing.

Eifler might have been even more upset if he’d realized something else: that contrary to what Donovan had told him, the plot against Heisenberg had not been canceled. Groves and Donovan had simply reworked it, enlisting other, less volatile hombres to carry it out.

One was Paul Scherrer. Code-named Flute, he worked as a physicist at the prestigious Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH) in Zurich, Albert Einstein’s alma mater. It was the ideal cover for an atomic spy. Switzerland had remained neutral during the war, so Axis and Allied citizens alike could travel there freely. Switzerland also bordered France, Germany, and Italy, which made it a convenient central location. Zurich became the epicenter of wartime espionage as a result, a hotbed of spies and double agents. Only a fool trusted the strangers he met in bars and cafés there.

Flute and Heisenberg had once been friends, and Heisenberg still trusted him completely. For Flute, things were more complicated. The war—and especially Heisenberg’s refusal to denounce German aggression—had driven a wedge between them. Flute didn’t cut off his friend entirely, but he did feel obligated to feed information about his whereabouts to the Allies, including his occasional trips to Switzerland. Two years earlier, in fact, in November 1942, Flute had invited Heisenberg to give a lecture at ETH on something called S-matrix theory. (It described how elementary particles collided; S stood for scattering.) This lecture had actually been the impetus for the original suggestion to kidnap Heisenberg in the first place. That plot had died of inattention, but as luck would have it, Flute invited Heisenberg back to ETH in the fall of 1944—and this time Groves and OSS pounced. Apprehending Heisenberg in neutral Zurich would eliminate the need for an Eifler-type raid into hostile territory.

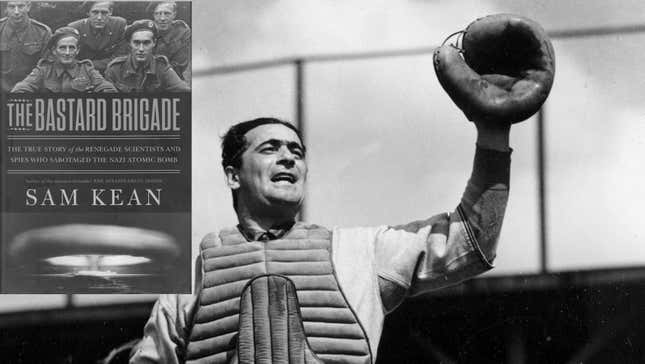

Besides Flute, the other agents enlisted in this plot were Samuel Goudsmit, a Dutch physicist, and the real star of the mission, a former Major League Baseball catcher named Moe Berg.

Casey Stengel once called Moe Berg the strangest person to ever play professional baseball—which is saying something. Berg had entered Princeton University at age 16 and joined the Brooklyn Robins (later the Dodgers) right out of college. He then played 15 Big League seasons, mostly with the White Sox, Senators, and Red Sox. But during the offseason he might, say, sail off to Paris to study medieval Latin at the Sorbonne. (You know, like most ballplayers.) During other offseasons, he earned a law degree from Columbia University. Berg spoke at least a half-dozen languages—some people said a full dozen—including hieroglyphics. He would buy dictionaries, he once said, “to see if they were complete.” He ate meals sometimes consisting of nothing but applesauce. He once polished off a book on non-Euclidean relativistic space-time in the bullpen during a doubleheader in Detroit. And when his flabbergasted teammates asked why, he explained to them that he was going to be calling on Albert Einstein the next time he visited Princeton, and wanted to discuss the matter more.

As you can imagine, reporters drooled over Berg. He was actually pretty mediocre on the diamond—fat and slow, and a crummy hitter. But he got more column inches than any benchwarmer in sports history. And in the 1930s he appeared a radio quiz show called Information, Please, the Jeopardy! of its day. In a virtuoso half-hour performance he answered questions about Halley’s comet, chop suey, Nero’s wives, poi, the Dreyfus Affair, and Kaiser Wilhelm, among other topics; he even got the trick question right. (What’s the brightest star in the sky? The sun.) NBC got 24,000 letters in response, and baseball commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis later told Berg, “In 30 minutes you did more for baseball than I’ve done the entire time I’ve been commissioner.” The added attention did chafe Berg some. During his rare appearances on the field, fans in opposing stadiums would heckle him with questions. (“Hey, Berg, is it walruses or walri?”) But after Information, Please, Berg was a bona fide celebrity, palling around with the Marx brothers and Nelson Rockefeller and Will Rogers. Whenever FDR attended a Senators’ game, he waved to the catcher from the stands

Berg loved baseball. He once told a reporter, “I’d rather be a ballplayer than a president of a bank or justice on the United States Supreme Court.” But world events soon compelled him to rethink that stance. Berg was Jewish, and had actually been visiting Berlin in late January 1933 when Adolf Hitler was elected the new chancellor; he then spent the day watching crowds of jubilant Nazis celebrate in the streets. And by the time World War II erupted in September 1939, he decided he had to fight the Nazis. He was a little too old for the military, but the OSS eagerly added the catcher to its ranks and turned him into a spook. On his first mission he parachuted into Norway, and later ran missions in Italy and France. But his most important mission involved seizing Werner Heisenberg in Switzerland.

The plot to seize Heisenberg called for Berg to slip into Zurich and make first contact. Goudsmit, who knew Heisenberg personally, would follow a few days later. Beyond this, details were sketchy. They talked sometimes of merely grabbing and interrogating Heisenberg before ultimately letting him go. Other times, they planned to spirit him away to Allied territory. In either case, they’d need more muscle: Berg and Goudsmit were hardly seasoned bounty hunters. And the plot would violate nearly every international law in existence about wartime neutrality. The Swiss tolerated spying unofficially, but you had to be discreet; you couldn’t shanghai Nobel laureates on the street. Indeed, one top OSS official in Switzerland (Allen Dulles) vehemently protested the kidnapping on these grounds, fearing that the Swiss would sever diplomatic relations with the United States and thereby endanger the entire U.S. intelligence apparatus abroad. But as happened so often during the war, fear of Adolf Hitler getting an atomic bomb overwhelmed every other rational consideration.

In preparation for the mission, Berg mostly behaved himself and—unlike his usual M.O. of going AWOL in the middle of mission—kept OSS informed of his whereabouts. It probably helped his mood that OSS advanced him more than $3,000 ($41,000 today) for hotel rooms and meals during those months, in addition to a 20 percent raise in salary, to $4,600, in anticipation of his dangerous assignment. To further placate the catcher, OSS officials did their utmost to keep him updated, via telegraph, on Major League Baseball standings.

The mission came together smoothly at first. Heisenberg accepted Flute’s invitation to lecture and they settled on a date in mid-December. Berg would attend the lecture and listen for clues about Germany’s progress with nuclear fission. Flute would then arrange a meeting between Berg and Heisenberg to establish contact, with Goudsmit joining later. Flute of course knew that Berg was working for American intelligence and wanted to feel Heisenberg out about nuclear bombs. But he assumed the meeting was a straightforward interview. He would have been horrified to learn that he was abetting a kidnapping. Suspecting as much, OSS kept him in the dark.

For his part, Heisenberg accepted Flute’s invitation for several reasons, none of them related to physics. He was feeling more isolated than ever from the world scientific community and longed to reconnect with an old friend. Visiting in mid-December would also give him a chance to pick up new winter clothes and better Christmas presents for his wife and children. As a neutral country, Switzerland faced no shipping embargo, and Swiss manufacturers (unlike German ones) didn’t have to divert all their energy into producing war goods, which meant that toys and chocolates and other treats were readily available in Zurich. In short, Heisenberg had visions of sugarplums dancing in his head, and had no inkling he was walking into a trap.

But the trap soon experienced a snag. In addition to Heisenberg, Flute had also invited a blueblood physicist named Carl von Weizsäcker to speak in Zurich on November 30. (Weizsäcker was the son of the number two person in the Nazi foreign ministry.) Weizsäcker knew that his visit would be controversial, given his father’s status, so he tried to mitigate his presence by lecturing on an innocuous topic, the evolution of the solar system. The ploy didn’t work. A mob of ETH students turned out to protest the Nazi’s son, and a riot nearly broke out. ETH officials had to lock the lecture hall for safety, and Weizsäcker returned to Germany shaken.

Hearing this, Heisenberg put strict stipulations on his appearance: the crowd had to be small, so he could speak freely, and only other physicists could attend. This presented difficulties for Berg, who as a six-foot-one, 200-pound non-physicist was likely to attract scrutiny at an intimate gathering. Still, Flute had no choice but to give in to Heisenberg’s demands.

Then, just days before the mission started, the plot endured another, more serious blow. Samuel Goudsmit suffered a mental breakdown and had to be cut out.

Paradoxically, going after Heisenberg with the gentle Moe Berg rather than the brutal Carl Eifler all but ensured that the mission would turn violent. To be sure, ever since OSS first enlisted Eifler, the plot had had an undertone of violence. Eifler, though, simply had permission to kill Heisenberg if things went south; his death had never been the point of the mission. But with Berg going solo, OSS had to abandon all hopes of a kidnapping: Berg would never be able to manhandle the physicist alone, and Samuel Goudsmit wouldn’t be there to interrogate him anyway. As a result, assassinating the physicist seemed the only viable option. Moe Berg would have to become a deadly hombre.

Although too unstable to accompany Berg, Goudsmit did help brief him in Paris on December 13, passing along final instructions from Groves. Berg was to take his pistol to Heisenberg’s lecture and listen closely to determine how much progress the Reich had made toward a nuclear bomb. It seemed unlikely that Heisenberg would just start blurting out threats, of course, but he might drop clues here and there, hints. If nothing else, the laddish Heisenberg might well brag in front of his peers. And if he did so, Berg had to render him “hors de combat,” as Goudsmit put it. That was more than a mere flourish of French between two polyglots. Literally, the phrase means “outside the fight,” or more colloquially, “out of action.” It usually refers to battlefield casualties, and as one historian noted, “There is a very narrow range of ways in which a gun may be used to take an opponent out of battle.” Five years earlier Goudsmit had welcomed Heisenberg into his home in Michigan for a physics conference there. Three years after that he’d proposed kidnapping him. Now he was telling another friend to shoot the man.

Heisenberg arrived in Zurich by train on December 16. Riding alongside him was Carl von Weizsäcker, who served as his official escort. Beyond that, Heisenberg had no security with him. What had he to fear in Switzerland?

In fact, news from the front lines soon put Heisenberg in fine fettle. The day he arrived in Zurich, the Third Reich launched its last major offensive of the war, now known as the Battle of the Bulge, in the dense forests of Belgium. To everyone’s surprise the Wehrmacht still had plenty of fight left, and the Germans knocked the Allies in the teeth and sent them staggering backward. The German press was ecstatic, and a few delirious reporters hinted that the Nazis might deploy atomic weapons soon, driving the Allies off the continent forever.

Heisenberg finally gave his lecture on the 18th, a week before Christmas. Despite the abundance of consumer goods there, Switzerland did ration fuel during the war, and the first-floor lecture hall at ETH was chattering cold. Weizsäcker had no doubt told Heisenberg about the near riot during his talk three weeks earlier, but thanks to Heisenberg’s insistence that the talk not be publicized, only 20 physicists showed up.

Plus a pair of spies. Berg entered the freezing lecture hall with a fully loaded Beretta concealed beneath his suit coat. Although just three months younger than Heisenberg, he was posing as a Swiss graduate student learning the intricacies of quantum mechanics. At Berg’s side was an OSS agent named Leo, sent to escort Berg and presumably help him escape after the deed. And if Leo failed, the catcher had a lethal cyanide pill in his jacket pocket. One sharp bite down, and he’d render himself hors de combat, too.

Berg took a seat in the second row and produced a small notebook and pencil, as if to take notes on the lecture. In fact he drew a map of the room and began taking notes on the other attendees. At one point he also tried out his German and offered his coat to a man seated in front of him who seemed chilly. Carl Friedrich Freiherr von Weizsäcker turned his deep-set eyes on the stranger and curtly told him no. Berg jotted “Nazi” in his notebook and fingered him as Heisenberg’s minder.

At 4:15 p.m. Berg finally laid eyes on the man he’d spent months obsessing over. Heisenberg emerged onstage in a dark suit, and after having some trouble cranking the blackboard into place, he wrote out several equations. While he did so, Berg took notes on his manner and appearance. It was a superfluous act—it’s hard to imagine Carl Eifler bothering—but Berg wanted to size up the man he’d emotionally prepared himself to kill. He described Heisenberg as looking “Irish,” with an oversized head, ruddy hair, and a bald spot on the crown. He wore a wedding band on his ring finger, and his furry eyebrows couldn’t quite conceal two “sinister eyes.”

His equations ready, Heisenberg began speaking, blithely unaware that his survival depended on what he’d say over the next few hours. He’d decided to lecture on developments in S-matrix theory, the scattering theory he’d first outlined at ETH two years earlier. Berg could not have been pleased with this choice of topic. Again, he didn’t expect Heisenberg to sketch a bomb on the blackboard and start cackling, but he must have hoped for something at least related to fission—a lecture on reactors, perhaps. Instead Heisenberg wanted to talk pure theory, especially his hope that S-matrix theory could reconcile quantum mechanics and general relativity.

He began by outlining a history of the topic. Berg noted that he paced as he talked, his left hand thrust in his jacket pocket. And despite the esoteric topic, Berg strained for any hint that Heisenberg might be betraying more than he realized. Do those equations relate to fission somehow? Is scattering important for chain reactions? At one point Heisenberg’s gaze lingered on the unibrowed stranger for several seconds; they might well have locked eyes. “H. likes my interest in his lecture,” Berg wrote.

No matter how hard he strained, though, Berg couldn’t decipher the equations. It all seemed like innocuous physics, but how could he be sure? Was he missing something? Doubt began gnawing at him, and his mind inevitably circled back to the most famous discovery of the man now pacing the stage. Berg scribbled in his notebook, “As I listen, I am uncertain—see: Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle—what to do.”

Meanwhile, the physicists in the room remained oblivious to Berg’s torment, focused on the equations. “Discussing math while Rome burns,” Berg wrote. “If they [only] knew what I’m thinking.” In truth, Berg himself didn’t know what to think. Failing to act could hand Hitler the Bomb, and Europe with it. (So do I shoot and potentially save the world?) Then again, could he really shoot a man without hard evidence—especially knowing that he’d sacrifice himself in the process? He could feel the gun heavy in his pocket, but as Heisenberg droned on, that other piece of OSS gear, the L-pill, must have weighed more and more heavily on his mind.

This private torture continued for two and a half hours. And in the end, uncertainty made up his mind for him. When the lecture ended, he still couldn’t bring himself to shoot.

Afterward, the score of physicists broke into small groups to chat, and a few rushed the stage to talk to Heisenberg. Berg took the opportunity to introduce himself to Flute, reciting a prearranged code phrase, “Doctor Suits sends his regards from Schenectady.” The two spies quietly arranged to meet later that night in Flute’s office.

Berg then crept close to the scrum around Heisenberg to eavesdrop, pretending to study the equations on the blackboard. Might Heisenberg let his guard down now, brag about something? No. After a bit of chitchat, a few old chums whisked Heisenberg off to dinner at the famous Kronenhalle café, leaving Berg behind in the freezing lecture hall. Having nothing to do, he skulked off to meet Flute—emotionally wrung out and still uncertain whether he’d done the right thing.

Heisenberg, meanwhile, was in high spirits at dinner. The lecture had gone well, he was surrounded by friends, and a newspaper story about the new German offensive left him so thrilled that he read it aloud at the table. “They’re coming on now!” he marveled. Oblivious as ever, he failed to notice that his hosts were mortified.

Later that week Berg got a second chance. Flute was holding a small dinner party in Heisenberg’s honor, and Berg hoped that, away from the seminar room, in a relaxed atmosphere with wine and food, some unguarded remark would betray the status of the German nuclear bomb program.

As with his lecture, Heisenberg put stipulations on the party, telling Flute that politics and the war were verboten topics of conversation. He had good reason for doing this. In the few days since he’d crowed over the newspaper article, the Battle of the Bulge had turned against Germany. The Wehrmacht certainly hadn’t been crushed, but the fighting had deteriorated into a yard-by-yard struggle amid snowdrifts and icy streams—exactly the sort of long slog that a depleted Germany could never win. Heisenberg’s grand, improbable dream—for a stalemate that would somehow both discredit the Nazis and keep the Allies out of his homeland—seemed less and less likely. Moreover, in the nest of spies and informants that was Zurich, he didn’t want to talk politics among strangers. Even at this late stage of the war, “defeatist remarks” could get you shot in Germany.

Flute agreed to Heisenberg’s demands, but as soon as the party started, Heisenberg realized the futility of this promise. Even if Flute stayed quiet, he had no control over his guests, several of whom cornered the physicist to pelt him with questions. Berg sidled up to listen, and it was ugly from the start. No one wanted to hear Heisenberg’s rationalizations, and when he began whining about how the world was demonizing the good people of Germany, the other guests jumped down his throat, reminding him who exactly had started this war. They also scoffed when Heisenberg claimed to know nothing of Jews and other undesirables disappearing from Germany in large numbers. (In truth he almost certainly knew that the precious uranium he was using in his atomic reactors came from processing plants that employed female slaves.) The guests backed down only when he stoked their fears about the Soviet Union: he argued that Germany was the one bulwark between civilized Europe and the hordes of Red barbarians eager to overrun it, a scenario that frightened your average Swiss even more than a German invasion. Heisenberg being Heisenberg, however, he managed to swallow his foot one last time near the end of the interrogation. Someone said, “You have to admit the war is lost.” Heisenberg sighed and said, “But it would have been so good if we had won.”

Heisenberg no doubt left the party exhausted and alone; all the residual joy from the lecture a few days earlier had dissipated. But as he donned his coat and stepped outside to walk home, someone joined him, someone he recognized from the lecture: the Swiss physics student with the heavy eyebrows. They were going the same way, it turned out, so he and Moe Berg—gun in pocket, pill in pocket—slipped off together.

As they walked, Berg pestered the physicist with questions. Drawing on his lawyerly training, he made several leading statements as well, trying to draw Heisenberg out. He complained about how boring Zurich was, saying that he’d give anything to be in Germany right now, where you could really fight the enemy. Heisenberg muttered that he disagreed but didn’t elaborate.

As they stalked the dark streets of Zurich, Berg continued to press and Heisenberg continued to parry: years of living under Hitler had conditioned him to guard his opinions, and he answered the “student’s” questions as vaguely as he could without being rude. Still, he had no inkling that this man was prepared to shoot him; even a jest, an ironic comment taken the wrong way, could have fatal consequences. Berg, meanwhile, had a perfect opportunity to carry out the execution. They were walking alone, at night; he easily could have ditched the gun and fled. So why not shoot Heisenberg, just to be safe?

In the end, uncertainty triumphed again: Berg simply couldn’t do it. The two men parted at Heisenberg’s hotel, and when Heisenberg turned his back one last time, Berg made himself walk away. Heisenberg entered the lobby and put the encounter out of his mind. Berg never could.

Heisenberg left Zurich the next day to spend Christmas with his family in Germany; he had toys for his children and skin cream and a sweater for his wife. To cut down on smuggling, Germany had banned the importation of certain goods from Switzerland, so Heisenberg had to pull the woman’s sweater over his shirt at the border and pretend it was his.

Berg continued to poke around Zurich for the next week, and he did pick up some choice bits of intelligence from Flute. These included claims of a “supercyclotron” in Germany that could separate fissile isotopes much faster than any previous method—exactly the sort of “kitchen sink” apparatus that Manhattan Project leader Robert Oppenheimer had warned that the Germans might come up with. Berg also confirmed earlier reports on the whereabouts of Heisenberg’s new lab.

Despite the praise these reports won him, Berg still felt tortured by doubt as 1944 came to a close. Fate had thrown him two chances to take out Germany’s top nuclear scientist, and he’d watched both pitches go by. Would he come to regret his prudence? Would the world?

Sam Kean is the New York Times bestselling author of several books, and has written for The New Yorker and The Atlantic, among other places. This excerpt is from his new book, The Bastard Brigade, which comes out today. You can buy it here.