BACKGROUND: CO-INNOVATION AS A FORM OF OPEN INNOVATION

/On October 27th, I have the pleasure of being the keynote speaker for North Carolina State University's Center for Innovation Management Studies Conference: Open Innovation - Revisited. They invited me to provide a bit of background in their blog series on the material I'll be covering. Here is a lightly edited version of that post: Co-Innovation as a Form of Open Innovation.

My basic premise is that 20th-century organizational boundaries and practices may be holding back our ability to innovate. The idea of open innovation is very 21st-century in that there is a definitional acknowledgment that innovations flow in and out of formal organizational boundaries. This likely makes great sense to anyone reading this post.

Benefits and Burdens of Open Innovation

Mark Spry, CEO of Pulse Mining Systems, a very 21st-century enterprise resource planning technology company (I've mentioned Pulse Mining Systems in an earlier post) has helped me understand their open innovation practices. A key to the company’s success is the foundational focus on co-innovation with its customers and partners. This is one type of open innovation and is very successful in Pulse's context.

However, in other contexts, we can see examples of tensions between the old and the new. Think about the challenges Uber, Lyft and even UpWork (merger of Elance and oDesk) face when it comes to organizational boundaries, like who is and who is not an employee. In that context it is the people doing the work who are flowing in and out of formal organizational boundaries. As long as benefits are tied to employment status — something that goes back to colonial times in the US — there will be friction in those flows.

What Pulse Mining Systems has done so well is to manage the people, the roles, and the technology (both the tools and the product), such that there is benefit to all parties for working together. Using the terms from my book, The Plugged-In Manager, they are mixing (negotiating) across the various boundaries and putting a priority on sharing/demonstrating to others the benefits of the co-innovation approach. Allow me to share a bit of the background here.

Definitions

As Hank Chesbrough, one of the foundational authors in the open innovation area, has noted that there is some confusion in our broad use of open innovation and related terms like, “open collaborative innovation.” Given my own expertise is in the application of open innovation rather than its theoretical foundations, I’ll stick with a recent definition offered by Chesbrough and his (and my!) colleague Marcel Bogers:

Open Innovation

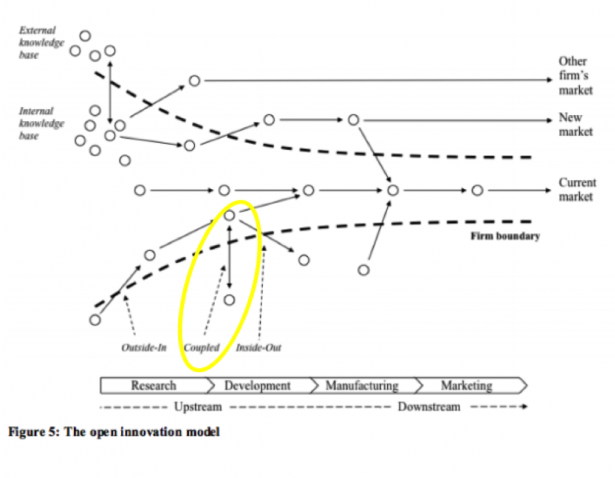

Open innovation is defined as, “a distributed innovation process based on purposively managed knowledge flows across organizational boundaries, using pecuniary and non-pecuniary mechanisms in line with the organization’s business model. These flows of knowledge may involve knowledge inflows to the focal organization (leveraging external knowledge sources through internal processes), knowledge outflows from a focal organization (leveraging internal knowledge through external commercialization processes) or both (coupling external knowledge sources and commercialization activities)….” (Chesbrough & Bogers, 2014). These knowledge flows are the building blocks and processes of innovation.

Just as a reminder, I offer Chesbrough and Bogers’ Figure 5 to highlight the particular focus of this post:

Co-Innovation

Co-innovation, or “coupled open innovation” in Chesbrough and Bogers’ terms, “involves two (or more) partners that purposively manage mutual knowledge flows across their organizational boundaries through joint invention and commercialization activities.”

Pulse Mining System engineers do not sit behind closed doors and design new enterprise software tools for their customers. Instead, they co-innovate with their key customers and vendors to build the tools that the customers need most and in a form that will be immediately valuable.

In the particular example Mark Spry shared with me, customer Centennial Coal and vendor Birst (a business intelligence and analytics company) played major roles. Centennial shared their needs. Pulse opened their already broad platform of software to components created by Birst. The new product was then offered to all customers with feature updates made possible much faster than they would have been if each of the groups had to work independently.

Lead by Letting Go

In prior posts, I’ve written about how we can lead by letting go (of old school management techniques), but that creates an image of chaos for some. Instead of chaos, imagine a structured handoff of responsibility. We are unlikely expert in all the areas where we need expertise. Co-innovation is a solution. Pulse has found like-minded partners in their customers and vendors (SAP has done the same with its co-innovation labs.) Each seems to have developed simple rules to handoff pieces of the innovation process to partners with appropriate skills.

Mark Spry offers that we, “can’t underestimate the power of shifting mindsets… to get that buy in and bring that data to life. Co-creation gets some of that end-user buy in from the beginning.”

In the keynote presentation at the CIMS Conference: Open Innovation – Revisited, I will suggest that many organizations need to let go of 20th-century boundaries and processes if they want to get full value from open innovation. Certainly we need to hold tight to our performance standards, relationships, education and the laws of the organization’s ‘physics,’ whatever those might be. However, think of these as the scaffolds that then let us open up organizational boundaries for co-innovation.

Shall we do a little co-innovation here? Do you have an example to share here and/or at CIMS Open Innovation — Revisited?