In the 1981 offseason, feeling underpaid and unhappy about Oilers owner Bud Adams’s treatment of former coach Bum Phillips, Earl Campbell asked for a raise. Only a year earlier, at the close of Campbell’s second season, the normally tightfisted Oilers had agreed to restructure Campbell’s rookie contract, adding performance incentives that could boost his pay to $3 million over six years. But they were immovable on the deferments baked into the original contract, the ones that doled out Campbell’s wages in paltry increments over a couple of decades.

The knowledge that he continued to be exploited rankled, in ways that made him rethink his relationship with the team’s management. “Everything for Earl became about money,” Witt Stewart, his new agent, told me. And so in January 1981, after another stellar year on the field and only a few days after Bum’s firing, he and Stewart approached the Oilers and demanded that Campbell’s salary be doubled, to $1 million a year—about $3 million in today’s dollars. Otherwise, Campbell threatened to sit out the coming season.

Trying to paint Campbell as greedy, the Oilers general manager alerted the press to Campbell’s ultimatum—“We won’t be blackmailed,” he said—and suddenly Campbell, whose persona was humble and affable, was on the defensive.

The contract negotiation—especially the holdout threat—was big news in Houston. This was in the middle of the Iran hostage crisis, and surveying the crush of microphones that greeted them at one of their contract negotiation press conferences, Campbell leaned into Stewart’s ear and whispered: “We’re bigger than the Ayatollah.”

“Campbell still doesn’t have the security he needs,” Stewart explained to reporters at the time. “Earl really feels God chose him, not his brothers, to take care of the Campbell family.” Earl had grown up in deep poverty in East Texas—the family had nailed up quilts on the walls of the shack-like home to keep the wind from blowing in—and he had spent a chunk of his first contract on building a new home for his beloved mother, a widow who had raised him and his 10 siblings. Stewart told reporters that Campbell had recently met with the financially troubled, scooter-confined former heavyweight fighter Joe Louis and that Campbell had told Stewart, “I don’t want to end up like Joe Louis.” And Stewart said that coming out of college, Campbell had “had as much chance as somebody who just landed on earth would have had against a slick real-estate salesman”—meaning Bud Adams, the Oilers owner, an oleaginous man once described as hippopotamus-like. “He bought the land without knowing to check for problems with earthquakes or mud slides.”

Campbell was a league superstar and was sacrificing his body weekly. But he was also being paid far more than the average NFL running back—who made $95,000 in 1980—and for the first time in his career, Campbell felt the sting of public and press criticism for his attempt to renegotiate a contract that still had five years to run. “Heroes don’t act that way, people said,” Dale Robertson reported in the Houston Post, with a heaping of wryness. “Davy Crockett wouldn’t have asked for a raise at the Alamo. Shame, shame.”

Some of the accusations of greed were tied up with race, and sometimes they veered darkly toward violence. One day, an FBI agent came by Stewart’s office with a warning. The agency had infiltrated the Houston-area Ku Klux Klan and learned that Stewart had been put on a list to harass or injure if given the opportunity. “The whole point was that I was trying to help Earl, a black man, get more money.” Stewart said the agent suggested he and Earl avoid a popular country-western club that they frequented.

That January, in a comfortable house in Houston’s Memorial neighborhood, a 60-year-old osteopath and his 29-year-old son got into an argument over Bum’s firing—and soon, they started shouting about Campbell’s contract. Lon Tripp, the son, an oilfield worker, thought Campbell’s demand was fair; his father, Franklin, thought the Oilers should trade anybody who asked for that much. Lon Tripp told his father he was like Bud Adams: “You want to make slaves out of people and have them work for you for nothing.” A homicide detective wrote in a police affidavit that the “father got fed up with the argument, went into his room, got a gun, put it in his coat pocket and sat down in a lounge chair in the den.” The detective said that the argument continued and that the son got up from the couch and walked toward the kitchen. The father then allegedly pulled out the weapon.

Young Tripp told his father, “either shoot that gun or I’ll make you eat it,” according to the detective. A .38-caliber slug hit the son in the chest, the detective said.

Franklin Tripp was charged with murder. At his trial that July, he said he had acted in self-defense, citing what he called his son’s drug-fueled rages. He said that at one point he had picked up the phone to call the police, but his son grabbed it out of his hands. In the end, a Harris County jury acquitted him.

Ultimately the Oilers held fast—and Campbell, eager to maintain his reputation, reported to training camp. “Money’s not the thing I’m after anymore,” Campbell said. “I don’t have a lot of it and I probably never will. That used to be one of my desires. But a man matures and learns a few things. If I had to say I deserved a little more, I’d say yes. But I don’t ever want to get in a situation where I have to argue with management to get it. I’m too old to be arguing with people.”

He was 26 years old.

“I think I love the game more now than I ever did,” he continued. “Only thing I hate about it is I love my wife and I hate being away from her. I’m always worried if everything is all right when I’m gone, and Southwestern Bell won’t give me no breaks. But, when I put on a jock strap, I get higher than train smoke.”

Even if Earl was still in the fold, Bum’s firing didn’t exactly solve the Oilers’ problems. Houston started the 1981 campaign 4–2, but fizzled out to finish 7–9. Campbell, though hobbled by injuries, compiled 1,376 yards—another monster year, but for the first time in four seasons, he didn’t lead the league in rushing.

Decades later, Stewart ran into Bud Adams in Nashville, and conversation naturally turned to Earl Campbell and an upcoming get-together of former Oilers that Adams was organizing. “You taught him well,” Adams, who died in 2013, told him. “He’s the only player who ever demanded money to come to a reunion.”

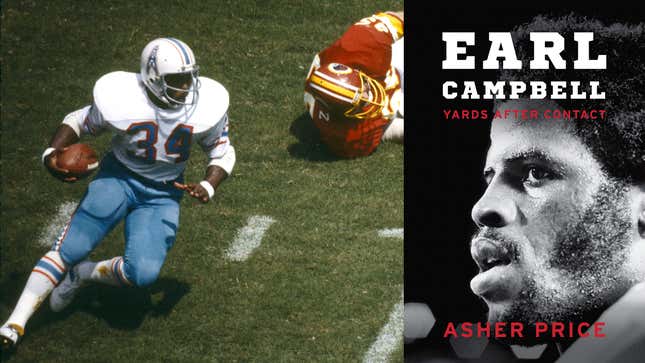

This adapted excerpt from Earl Campbell: Yards After Contact is published with the permission of University of Texas Press.

Asher Price is a staff reporter for the Austin American-Statesman and a journalism fellow at the University of Texas Energy Institute.