Any self-respecting student of insane Machiavellian gambits should be familiar with the Madman Theory, Richard Nixon’s self-invented strategy for winning the war in Vietnam. The theory, as recounted by Nixon chief of staff H.R. Haldeman after he got out of jail for his role in Watergate, went like this:

“I call it the Madman Theory, Bob. I want the North Vietnamese to believe I’ve reached the point where I might do anything to stop the war. We’ll just slip the word to them that, ‘for God’s sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about communism. We can’t restrain him when he’s angry—and he has his hand on the nuclear button’ and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.”

Historians will note that this did not work out so well.

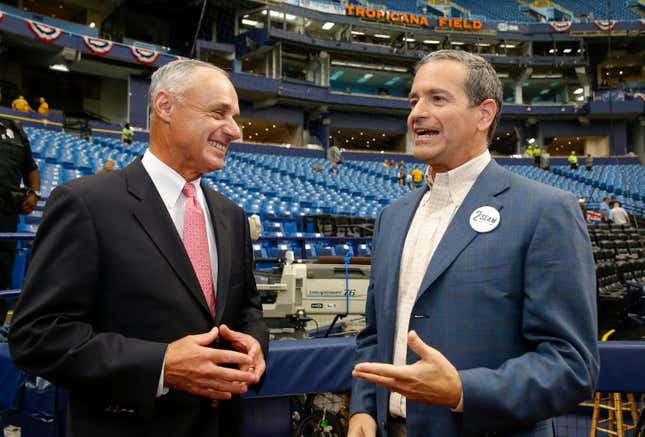

Which of course brings us to Stuart Sternberg, and the current lunacy gripping the Tampa Bay Rays franchise. Last week, the Rays’ owner, who has been trying and failing and failing and failing for years to get someone to buy him a new stadium somewhere in the Tampa Bay region, confounded the sports world by receiving MLB approval to pursue two new stadiums, one in Florida and one in its close neighbor, Montreal. By playing games in the south when it’s cold and up north when it’s warm, the idea went, Sternberg could maximize two fan bases’ willingness to leave the house to watch baseball, and replicate the adaptive strategy invented by birds (though unlike the Rays, our feathered friends apparently started in the north and worked their way south).

This week, Sternberg doubled down, holding a press conference where he expounded at length on how this wasn’t a leverage move, how he is totally serious about playing home games in two cities separated by 1300 miles and one international border impervious to chocolate eggs, and how doing so would “spawn an economic impact” from Canadians visiting Florida in the spring, but somehow not an economic drain from Floridians visiting Canada in the summer, because economics, okay?

There are many, many reasons why this is unlikely to work—building two new stadiums would cost more than one even if the annual migration meant they could forgo roofs; two fickle fan bases would have even more reason to ignore the local half-team if it was forever packing its bags to leave; players would balk at having to pick up and move their families every June—most of which were already expounded on by Barry Petchesky last week. (FanGraphs’ Jay Jaffe further notes that neither city has a stellar MLB attendance record, and Montreal already has bad experience with one team timeshare scheme.)

Sternberg, though, doesn’t need a two-country solution to work. He only needs for people to think he thinks it will work. As Nixon tried to do in Vietnam, he’s counting on L’Affaire Montréal serving less as a legitimate threat to half-move and more as a sign of how far he’s willing to go to get what he wants.

Let’s look at this from the perspective of Sternberg. (For this exercise please don your open-necked pastel shirt and stuff your wallet with hundred-million-dollar bills.) In May 2004, the former vampire squid henchman spent $200 million to buy controlling interest in the Rays, who were at the time six-plus years into an experiment as to whether Florida sports fans would turn out en masse to watch a team that had never finished higher than last. (That hasn’t gone great, either.)

Bound to the hideous and inconvenient Tropicana Field by a use agreement (like a lease, but with bigger teeth) that prohibited him from even talking to any other cities on penalty of a court injunction, Sternberg was stuck: His only options were to negotiate for a new stadium in a city fans hate traveling to and which showed no interest in lavishing untold tax money on him, or to wait until 2028, by which point he would be almost 70 years old and have spent the prime of his middle age watching his baseball team play in relative privacy.

Option three, of course, would be to spend his own money on a new stadium, but you don’t get to be a hundred-millionaire by spending your own money.)

Sternberg’s first move was to arm-twist St. Petersburg Mayor Rick Kriseman into granting him a three-year window to negotiate a stadium deal across the bay in Tampa, in exchange for a small buyout payment if he succeeded. This was a great idea in theory, but it blew up in Sternberg’s face when Tampa turned out not to have the revenue on hand to provide as much stadium cash as he wanted (i.e., almost all of it), leaving him to come crawling back to St. Pete with another nine long years of Trop lease to go.

We may never know the name of the city lawyer who wrote that use agreement back in 1995, but including a clause that the city could seek an injunction against even talking about a move, on the grounds that this would “result in irreparable harm and damages that are not readily calculable” was a genius move that shifted all the negotiating power to the city as long as the agreement was in in force. But if talking to other cities was verboten, talking about talking was another story entirely.

And here’s where we get back to Nixon’s madman: Sternberg doesn’t have to be serious about splitting time between two cities, or even about moving to Montreal at all. (It’s tough to compare U.S. and Canadian market sizes because the two nations calculate them differently, but Montreal’s metro area has about four million people, Tampa Bay about three, and as noted, both have a history of poor attendance in unloved stadiums; games in Montreal would also have the disadvantage of selling tickets in loonies, which are currently worth about 76 cents on the dollar.) Rather, he just has to make outside observers think he’s serious, despite the seemingly obvious stupidity of such a move—and what better way to show the world that you’re a deranged millionaire than to hold a press conference where you talk about how you love Sandy Koufax so much that you named your son after him and love St. Petersburg so much that you would like to spare locals from having to watch baseball all summer?

So what happens next? Under normal circumstances, a team owner would fly to Montreal to eat some bagels and pretend to speak French, the better to drive home how serious he is about considering part-time emigration. But that route would almost certainly trigger that injunction clause — indeed, Kriseman has already noted that the Rays can’t move anywhere before 2028 without his say-so, calling the current public uproar “a bit silly,” and then made his city attorney sit and watch the Sternberg press conference video to see if the Rays’ owner said anything actionable.

Still, an uproar is an uproar, and coming off as too unhinged to risk crossing may seem a better option to Sternberg than sitting back and waiting. If nothing else, it may get Kriseman thinking that he’d be better off taking some buyout money and the right to redevelop the potentially valuable Trop site than putting up with another eight years of this nonsense.

Or Sternberg’s ploy could go nowhere, and one day we could remember the ExRays as another odd footnote in stadium shakedown history, along with the contraction of the Minnesota Twins and the San Diego Padres’ floating stadium. So far the signs are mixed—even as Kriseman has been rattling breach of contract sabers, he’s also extended an offer to work on a new St. Pete stadium, so long as Sternberg knocks off this two-cities talk. But as any teenager or U.S. president can tell you, sometimes it’s more important to get attention and less important what kind of attention it is.

Neil deMause has covered sports economics for more publications than even he can shake a stick at. He’s co-author of the book Field of Schemes: How the Great Stadium Swindle Turns Public Money Into Private Profit, and runs the website of the same name.