WILDWOOD STATE PARK, N.Y. — Matt Borden, a plant pathologist, had walked less than 50 yards into the forest when he froze in place and looked skyward.

He was standing in a thicket of beech trees in mid-July, but their leaves were almost all gone. Those still remaining were crinkled and leathery — a telltale symptom of a parasitic worm wreaking havoc in forests stretching from Maine to Virginia.

“This is depressing,” Borden told his colleagues, his eyes still fixed on the sparse canopy overhead.

The spotted lantern fly has dominated public attention in the United States, with local and federal government agencies mobilizing campaigns to, literally, stamp out the brightly colored bugs. But a different pest is killing trees and confounding scientists, and it has received precious little attention.

Beech leaf disease has quietly raced across the country infecting a particular species of trees critical to forest ecosystems, the American beech. The mysterious condition has been shown to be caused by a newly discovered subspecies of nematodes, or microscopic worms.

First discovered in Ohio in 2012, beech leaf disease has now been identified in 12 states, where it’s ravaging trees in forests and back yards and costing nursery owners millions. But much remains unknown about the disease, namely, how are the nematodes spreading so rapidly and what, if anything, can be done to stop their march and save the infected trees.

“It could have a huge ecological impact,” said Mihail Kantor, an assistant research professor of nematology at Pennsylvania State University.

Kantor is among a small group of researchers who are studying the disease. Every three months, a few dozen plant pathologists, professional arborists and other experts jump on a conference call to discuss their work and trade ideas.

Despite concerns that the arboreal ailment could wipe out one of America’s most iconic trees, the scientists have struggled to get funding from government agencies and other sources to launch more of the kind of intensive studies they say are sorely needed.

“One of the main things we say on the calls is, ‘Oh, gee! You can’t find any funding,’” said Margery Daughtrey, a plant pathologist and senior extension associate at Cornell University’s School of Integrative Plant Science. “It’s a real problem.”

She noted that the spotted lantern fly, on the other hand, has drawn outsize attention and research money.

“Nothing against the spotted lantern fly,” Daughtrey said, “but it doesn’t actually bother people, and it doesn't bother many plants.

“This is threatening to eliminate an important Northeastern tree species,” she said.

Microscopic menaces

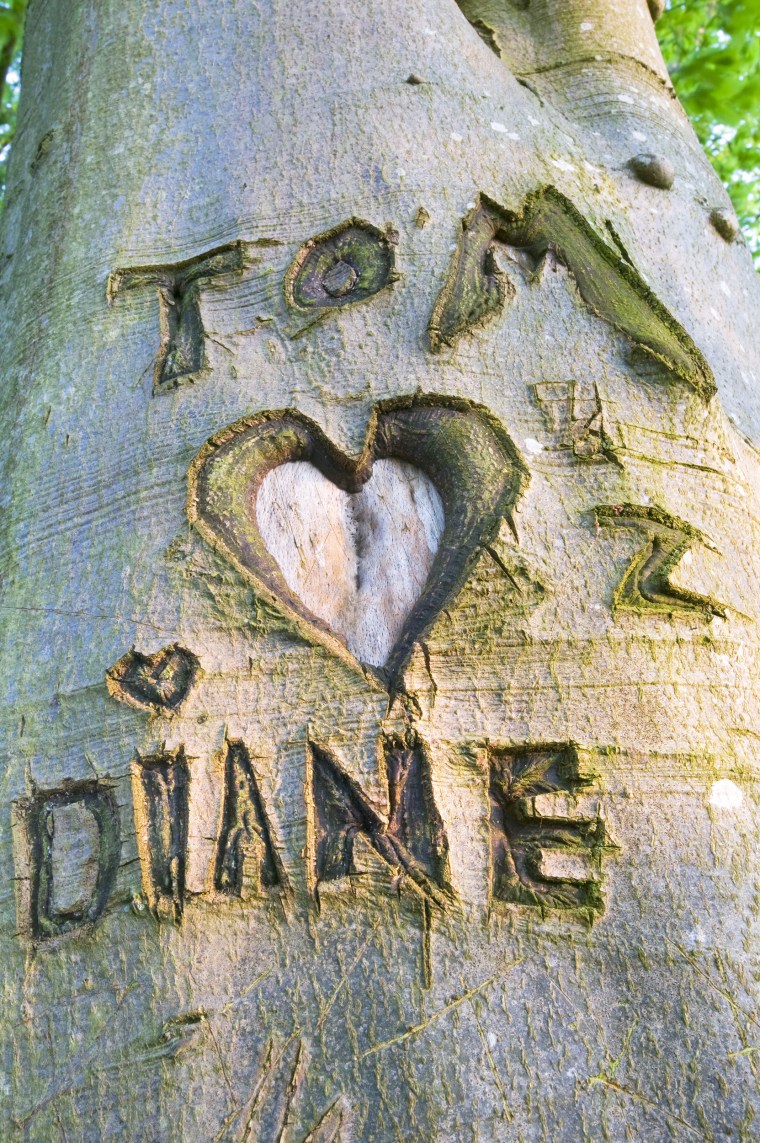

Beech trees are easy to spot.

They have smooth, gray bark and wide, easy-to-carve trunks, which have long proven irresistible to young couples looking for a place to memorialize their relationships.

The trees are considered a “foundational species” in northern hardwood forests. They produce a high-fat nut prized by bears, turkeys and other animals. And their towering canopy and trunk cavities provide a home for numerous types of birds and insects.

Beech trees are believed to be especially critical for black bears. Studies have shown a direct link between a healthy American beech forest and black bear birth rates.

In the years after the disease was first discovered, scientists had no idea what was causing the beech tree leaves to develop dark green bands and then to curl and pucker.

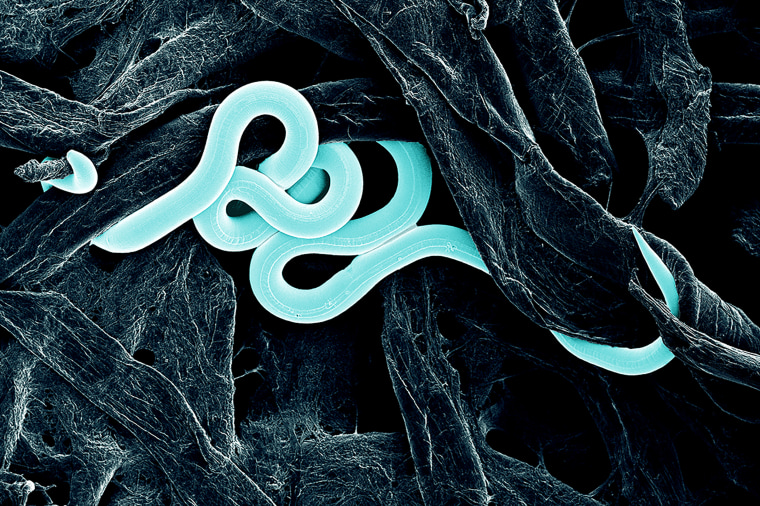

But in late 2017, a plant pathologist in Ohio, David McCann, was studying infected beech leaves under a microscope when he saw what he first thought were tiny leaf hairs. Then he noticed that they were moving — a eureka moment.

They were not hairs, but nematodes.

It was, in fact, a new subspecies now known as Litylenchus crenatae mccannii. The last part of the name honors McCann, a former pipefitter who went to college at age 30 and eventually attained a doctorate in plant and soil sciences from West Virginia University.

“I’m just glad I found the problem,” said McCann, who works for the Ohio Department of Agriculture.

But since then, the microscopic menaces have only caused more damage.

Danielle Martin, a forest pathologist for the U.S. Forest Service, said she realized just how devastating the disease can be when she returned to an infected area in Cleveland last summer, three years after first visiting the site.

“It was shocking how much it had advanced within those stands,” she said. “It was just dark, dead forest. I think my jaw dropped.”

The nematodes feast on the buds and leaves of beech trees. As the parasites multiply, the leaves develop dark bands, crinkle and thicken. In time, the buds die and the crown of the beeches thin out, hampering photosynthesis and hastening the trees’ death.

The nematodes have proven both alarming and fascinating to the researchers studying them.

No other leaf-eating nematode is known to infect a large forest tree in North America. The vast majority of nematodes dwell in the soil and attack roots or underground crops such as potatoes and carrots.

Plant pathologists recently discovered another unique characteristic: The beech tree-attacking nematodes cause cellular damage in the trees similar to the effect cancer cells have in mammals, according to a new study led by the U.S. Agriculture Department’s research arm, the Agricultural Research Service.

“This destructiveness and spread is completely new for a leaf-infecting nematode,” said Lisa Castlebury, research leader for the service.

Scientists are still working to answer a host of vexing questions.

Where did the pests come from (researchers suspect Japan)? Are other organisms involved in sickening the trees? And how have the nematodes spread so far so quickly in the U.S.?

One theory being studied is whether they hitch rides on birds or insects.

“The clock ticks rapidly against us given the unprecedented pace at which the nematode spreads,” Kantor said. “Increased funding could expedite our research, and as they say, time is money. In the context of BLD, time is of the essence,” he said, referring to beech leaf disease.

American beech trees grow from Ontario all the way down to Florida, so the disease has the potential to spread much farther.

The USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, or APHIS, has allocated more than $108,000 for a research project studying the risks of beech leaf disease in several states.

But it didn’t take more aggressive action because “at the time of its detection, the nematode was determined to be too widespread to establish an effective federal quarantine,” said Stephen Lavallee, national policy manager for APHIS.

"There are many uncertainties related to beech leaf disease and its transmission," Jo-Ann Bentz-Blanco, director of pest surveillance and emergency management for APHIS, added. "This limits what APHIS can do under the authority of the Plant Protection Act."

Some plant pathologists said they have no doubt that the disease would be attracting more attention and research money if it were affecting a tree that was more valuable to the timber industry, such as oaks or pines.

But the disease has already cost John Verderber a bundle. He runs Verderber’s Nursery and Garden Center in Riverside, New York, where European beech trees sell for up to $30,000.

The trees have long been sought out by well-heeled homeowners drawn by their beauty and grandeur.

Verderber estimates that the disease has cost him more than $1 million in lost revenue and labor to remove diseased trees.

“If we can’t sell these things, we have to cut them down and spend yet more money to get rid of them,” he said, standing among a plot of infected trees.

“Finding a cure would be wonderful for us nursery guys,” Verderber said.

On a steamy Thursday last month, a handful of plant pathologists and arborists walked from tree to tree at his garden center, inspecting their leaves.

Most of the researchers worked for Bartlett Tree Experts, a private company with a research arm and laboratory based in Charlotte, North Carolina. The group included Borden and his colleagues, Andrew Loyd and Beth Brantley.

They’re among a select group who are hunting for a beech leaf disease treatment, and Verderber was eager to allow them to run tests at his nursery.

For more than four hours, the researchers tagged the infected beech trees and recorded the percent of leaves with symptoms and the amount of canopy thinning.

In the coming months, a member of the team will return to apply a fungicide known as Broadform, plus one other experimental treatment. The site will be monitored to gauge the chemicals’ effectiveness at killing the nematodes before they move into the developing buds.

“We’ve had excellent results in lab assays and toxicology work, but field testing is tricky, and we continue to learn,” Borden said. “Some sites showed a dramatic reduction in nematode numbers and improvement in beech health, while at other sites, BLD progressed seemingly unabated.”

Daughtrey, the Cornell University professor, stopped by the nursery to see what the symptoms looked like in its European beech trees, a particular interest of hers.

“It’s nice that a private company has enough vested interest in doing this right,” she said, referring to the Bartlett researchers.

“We need many researchers asking these sorts of questions — not just a few — because the level of the problem is extreme,” Daughtrey said.