NASA compared twin astronauts to see if space ages the human body

Astronaut Scott Kelly spent nearly a year at the International Space Station.

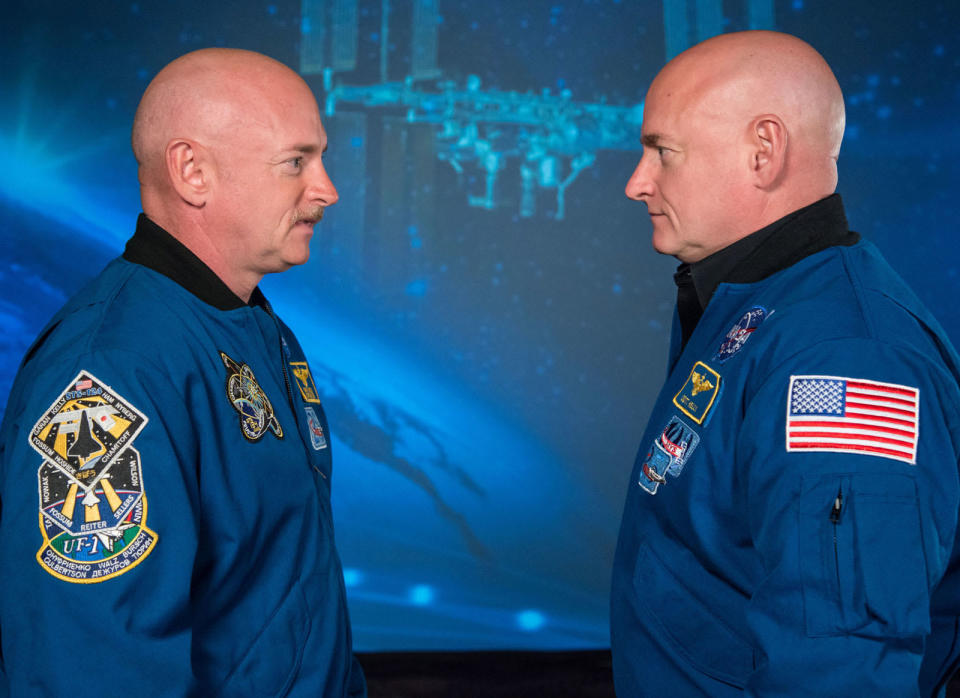

A NASA study that compared two twins, one who finished a nearly year-long mission in space and one who spent that time in Earth, found that most of the dramatic changes that happen to the human body in space aren't permanent. Scott Kelly, who was aboard the International Space Station between 2015 and 2016, experienced many physical and genetic changes that his twin brother and fellow astronaut Mark Kelly, who was back on Earth, did not.

But once the Kelly brother who was in space landed, his body gradually returned to normal. Some negative impacts from the mission still linger on Kelly, posing a challenge for scientists as they explore longer space flight, such as travel to Mars.

"If you look at the changes we're seeing in Scott, the vast majority of them came back to baseline in a relatively short period of time when he came back to Earth," said Steven Platts, deputy chief scientists at NASA's Human Research Program, at a press conference held by NASA on Thursday to discuss the findings. The full NASA twins study was published Thursday in Science.

NASA discovered that the telomeres of the Kelly brother who was in space got longer. Telomeres, which are the protective caps on the ends of chromosomes, get shorter as humans age. The discovery shocked scientists at NASA's Human Research program, who had decided to use telomeres as a way to measure aging. Lengthening telomeres is currently being studied by scientists as a way to reverse aging and beat cancer. Scientists aren't sure why the telomeres of the Kelly brother who was in space got longer, and are interested in finding out why moving forward.

Also surprising was that after Kelly returned to Earth, his telomeres began to shrink and got even shorter than they were before he began the mission. Shortened telomeres are linked with aging and disease. Susan Bailey, one of the study's co-authors, said the study was the first time telomere length was measured in astronauts.

Physical and mental changes also happened. A year in space lead Scott Kelly to become more farsighted as his carotid artery and retina thickened, which is common during space flight. He described his legs as "swelling like watermelons" every time he got up. There was also a shift in gut microbes and gene expression changes. All of these changes returned to stable or baseline levels after he landed, though some DNA damage and T-cell activation still remain. Kelly's cognitive abilities also declined after a year in space, a change that persisted even six months after landing. Kelly was given a flu shot while in space, and his body responded exactly the way it would have on Earth, a test that provides evidence that the immune system isn't affected during spaceflight.

Scientists thinks the study sheds light on how the human body can adapt and recover from the dramatic toll of spaceflight. The research can also help us understand how the human body reacts to other stressors, such as disease. "The Twins Study demonstrated on the molecular level the resilience and robustness of how one human body adapted to the spaceflight environment," said Jenn Fogarty, chief scientist for NASA's Human Research Program.