This year, the only American team in Formula One debuted with a new look and a new title sponsor. Rich Energy, an “elite” energy drink for “the discerning customer,” stands proud as Haas F1’s partner for the 2019 F1 season. But few can find Rich Energy for sale, and people are having an even harder time finding out where the company’s money comes from—or if it has any at all.

The Australian Grand Prix in March marked the start of the 2019 F1 season and Rich Energy’s debut as the black-and-gold full-car sponsor plastered across the cars of the up-and-coming Haas F1 Team. (Just a few weeks later, the company announced it would also sponsor driver Jordan King in the Indianapolis 500.)

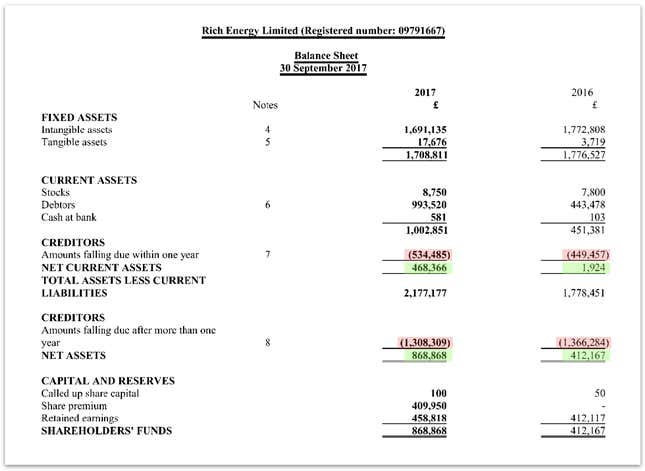

But heralding the arrival of Rich Energy Haas F1, UK financial documents popped up online showing Rich Energy as having 581 pounds (about $770 U.S., at current exchange rates but without accounting for inflation) in the bank in 2017, up from all of 103 pounds ($134 U.S.) the year before.

For some perspective, Haas is estimated to have an annual budget for its F1 team of $123 million, according to a Forbes report from 2018, and that’s just the relatively small Haas team alone. F1 in general is a series so expensive, so awash in sponsor money, that teams have spent $500 million in a year just to finish second. The gulf between what F1 costs and what Rich Energy outwardly looks to be bringing to the table has more than a few fans wondering what’s going on.

The further people went down the rabbit hole on Rich Energy, the weirder things got. America’s F1 team might just be partnered with a company without the means to sponsor it, fueled by a flipped Zimbabwean tobacco farm and investments from a soft-core porn billionaire. It’s charming, in the context of Rich Energy’s brand.

“Forget the wings,” the main page of its website proudly instructs visitors in a dig at Red Bull, “Rich Energy gives you horns.”

Is Rich Energy a scam? asked a Reddit thread in August. “Is anyone worried about the legitimacy of Rich Energy now that they are actually in Formula One?” read the title of another redditor investigation, soon after Haas announced it as the team’s title partner in October. “What is Rich Energy?” wondered another soon after, as did users on an Autosport forum post. Tweets started springing up mentioning the company’s financial documentation.

Rich Energy, of course, dismissed those questions outright.

The company’s CEO, William Storey, told Motorsport.com back in February that claiming his company doesn’t exist is “like saying man never walked on the moon, or Elvis is still alive.”

In a more recent phone interview, Storey told Jalopnik that everyone’s “been looking in the wrong place” for information about his company, and that the UK documents tell an “irrelevant” part of the story. Because Rich Energy is an international brand, he said, the UK financial documents only show part of his company’s finances.

He also told Jalopnik that Rich Energy is now in nearly 40 countries.

“It’s puzzling that people are seeing a company that’s growing very quickly, that’s working very hard, that’s got nice people involved, and rather than applauding us, there are some people who want to criticize us or find fault with us,” Storey said. “It is unreasonable, but I’m sure in the fullness of time, people will change their opinions.”

It has already been half a year since the world asked “What the hell is Rich Energy, anyway?” and yet we still don’t have a clear picture.

The notoriously gruff Haas team principal Guenther Steiner also rejected the skepticism about Rich Energy with a vague explanation, telling Autosport in October that the team had done its due diligence before meeting Storey, and that its legal advisors were content with it. “We did what we need to do. We needed to do it before we met him,” Steiner told Autosport. “Why do you doubt that?”

Public records, however, paint Rich Energy as an enigma, with traces scattered across the UK, Croatia, and Austria, and names that knot up in a circle of failed former businesses—some of which curiously echo Rich Energy’s current state.

Storey was eager to hype his young brand as innovative, creative, and with unorthodox marketing—all the typical tag lines—over the course of Jalopnik’s phone interview. But much of the reality of Rich Energy remains unclear, since Storey told Jalopnik he couldn’t publicly clarify every question around its financials and business model. He wanted to “give as much information ... as possible” without getting “commercially sensitive,” he said.

Sensitive information or not, this whole focus sprung up when the internet realized few people had seen or gotten their hands on a can of Rich Energy—even in its branded home base of the UK. Online, cases are available to ship to UK addresses through the company’s website, but that’s about it.

Of course, Storey has an answer for that, too. But many questions remain, making for a perfect example of what you find, and who you find, when you lift the veil on the money in Formula One.

The Money and the Business Model

The biggest mystery about Rich Energy is where it gets its money. The product isn’t widely available and partnering with an F1 team isn’t cheap, so it has to be coming from somewhere, right?

Companies House is the British registrar for corporations, and it requires businesses like Rich Energy to file the basics annually or each time something big happens. On Companies House, you’ll find information like incorporation date, annual returns and changes to the company, as noted on its website. The returns show a fairly general snapshot of company finances, as seen in the document below.

Aside from that aforementioned listing of 581 pounds in the bank, balance sheets filed with Companies House show Rich Energy as in the black in net assets—as of late 2017, at least.

Storey dismissed the balance sheet as “pretty irrelevant,” telling Jalopnik the balance sheet shows financial data from 2016 because of how documents are filed with Companies House.

“We now have considerably in excess of eight figures in our bank account at any one time,” Storey said. “So, that snapshot from 2016, which was effectively a startup company at that stage, is really completely meaningless. That was almost before we were getting started.”

Storey recognizes Rich Energy’s start date as when he began to develop the brand as a British drink. Now, Rich Energy claims to have been “painstakingly developed” over the past six years in online descriptions. But there’s more to the story if you trace things farther back.

The Rich d.o.o. trademark, which appears on cans, was registered in Croatia by an entrepreneur named Dražen Majstrović back in 2011, but Rich Energy was incorporated in the UK on Sept. 23, 2015 as per Companies House. Its directors at incorporation were current CEO Storey, Zoran Terzic (listed as a “Keep Fit Instructor” on Companies House), and a Richard Fletcher. Storey held all 50 shares at incorporation, and Fletcher was terminated as a director in 2017.

That starts to cover things up to 2017, but Storey declined to send over more current documentation that would eventually be made public with Companies House. He said the information was confidential, but thinks it will “very quickly become apparent that [Rich Energy is] very significantly bigger than one set of accounts from 2017 shows.”

Rich Energy has a “cutting-edge” manufacturing facility costing roughly $65 million at current exchange rates, and its cans are made in the UK, according to the company’s website. Storey provided Jalopnik with the address of the facility it uses to manufacture cans on the condition that its location be kept confidential, and said that the cans are then filled with the product in Austria.

And, like its product, Rich Energy’s money seems to have come from an amalgam of sources.

Again, Rich Energy’s trademark goes back to Majstrović in 2011, but because of his tenuous online presence, it’s not totally clear where the initial funding came from.

(Jalopnik did turn up an archived page from 2013 advertising Rich Energy, with a black and gold can in front of a nightclub. We cannot say for certain if this is all one and the same Rich Energy, but its advertising language purporting to be “conceptualized in Croatia” but “manufactured in Austria” lines right up, as does its promise that it was “poised to make a stunning debut on the Energy Drink Market in the United States.”)

As for Storey, his money comes from an unconventional source, he told The Telegraph last year—flipping a Zimbabwean tobacco farm:

Relying on his intuition seems to have served Storey well. When working in Zimbabwe on a tobacco farm, he spotted that a flood of Chinese businessmen were descending on the country and wondered why. He soon discovered that the value of land had been pushed artificially low because of political strife around controversial land reforms.

“A farmer I knew had a farm which had been worth $30m but was only worth $2m even though the amount of money being earned from the sale of tobacco was vastly more than that,” he remembers.

Storey invested in the farm – ownership wasn’t possible because of the reforms which stated landowners had to be Zimbabwean – and has essentially funded Rich Energy by “cashing in his chips” in the venture.

Developing a drink brand is one thing, money wise, but funding an F1 team is entirely another, depending on how much Rich Energy is actually putting into the Haas team.

Enter billionaire David Sullivan.

Sullivan is somewhat of a controversial figure. He and partner David Gold own the West Ham United Football Club, but before that, both Sullivan and Gold created a pornography empire together. The men started by selling mail-order soft-core porn photos, and slowly progressed into opening sex shops, publishing adult magazines, and producing pornographic films.

Sullivan was convicted in 1982 of living off of “immoral earnings”—that is, funds acquired through prostitution—and spent 71 days in prison. That didn’t slow down his acquisition of an impressive fortune, and certainly didn’t dissuade a partnership with Rich Energy decades later. Just before the Haas deal in 2018, Storey announced on LinkedIn that Sullivan “acquired a significant stake in Rich Energy.”

Rich Energy’s website says it “recently launched in the UK and U.S.,” but the product isn’t exactly easy to find—Jalopnik even sent six people in the UK looking for it in grocery and convenience stores, and each came back empty handed.

Storey told Jalopnik that’s a feature and not a bug, so to speak, explaining that his company went an unconventional route with distribution, targeting clubs, bars, hotels and high-end wine shops first—building the brand before the distribution and avoiding the long pitch and sale process with bigger retailers, he said. Retail partners are in the works, Storey said, but wouldn’t elaborate because they haven’t been announced yet.

“People are going to start seeing us a lot more in the more conventional environments—petrol stations, supermarkets,” Storey said. “I suspect that once that happens, a lot of these questions are going to start going away.”

Storey said “hundreds” of individual pubs and nightclubs stock Rich Energy in the UK, and that it has distributors worldwide. He mentioned a U.S. distributor—an entrepreneur—who just got 5 million cans, and the distributor’s website lists it as selling Rich Energy in six locations in Indiana, four in Virginia and one in Pennsylvania. Of the three Jalopnik called, two confirmed that they stock it.

Storey told Jalopnik Rich Energy has sold more than 100 million cans since he started the company in 2015. To put that into a bit of perspective, according to Forbes, Red Bull sold 6.3 billion cans across 171 countries worldwide in 2017.

But Rich Energy doesn’t see itself staying a minor player. Storey is nothing if not ambitious, at least in how he describes his operation.

“There’s been a race to the bottom with energy drinks,” Storey told Jalopnik. “Everyone’s accepted that Red Bull is the dominant party and that they need to find a niche in this market. We haven’t done that.”

In retrospect, Rich Energy in F1 makes perfect sense. A seemingly multinational company offering a slippery product, backed by a soft-core porn billionaire and someone who made money profiting amidst political strife and Zimbabwean economic, cultural, and societal turmoil. What could be more stereotypically F1?

Rich Energy Enters Formula One

Rich Energy made its first big waves in F1 when the Force India team went into administration in 2018. (Force India became Racing Point, after its boss ditched F1 amidst a billion-dollar debt case and charges of money laundering.) It was Rich Energy that came seemingly out of nowhere with an offer to save the team, though Storey claimed the deal was six months in the making, Motorsport.com reported.

Rich Energy’s pitch didn’t work out, as Eurosport reported:

This offer was dismissed and the team was placed in administration, which Rich Energy called a “tragic and avoidable outcome” and labelled the involvement of Perez, Mercedes and BWT “disgraceful”.

Autosport understands the offer from Rich Energy, which had previously been dismissed by the team as a credible outright buyer, involved two £15 million installments and was viewed as insufficient to guarantee the long-term future of the team.

Storey was adamant that this figure was incorrect and an order of magnitude low, but provided no evidence of his claim. Jalopnik reached out to confirm it with the team in question, but has not heard back. Regardless, the team went to driver Lance Stroll’s billionaire dad—another entertaining glimpse into who gets what in F1.

Storey said last year that his consortium was backed by “four sterling billionaires,” as Motorsport.com reported, including Sullivan and Gold, and that they had a contract to buy Force India in May of 2018. When asked about Sullivan and Gold, Storey said he’s friends with them and learns from them, since they’re “fantastic businesspeople.” A representative for West Ham United did not confirm their investment into Rich Energy, and directed Jalopnik elsewhere for the answer.

A LinkedIn post from Storey dated October of 2018, however, says that Sullivan had acquired an undisclosed but “significant” stake in Rich Energy.

When Force India went to Lawrence Stroll, Storey said that Rich Energy would be in F1 “sooner or later” because it had “the money to do so, the business model and the reasons to do it,” according to Motorsport.com.

Rich Energy courted the down-in-the-dumps Williams team for a time before the Haas deal happened, as noted by The Drive, which said Haas was willing to adopt Rich Energy as a title partner for half of Williams’ asking price.

This doesn’t appear to have been reported elsewhere, but it’s important to note that Haas is a CNC machining company that can, in theory, support its own race cars—as evidenced in both F1 and NASCAR.

The point of the team is, as Autosport reports, to promote its own CNC products—the support of a third-party brand doesn’t seem like something it needs.

The Haas deal came together rapidly, and it was in October 2018 when Haas announced Rich Energy would be signing on as its title partner. It isn’t clear what Rich Energy is paying Haas or how long this deal will last, although The Drive notes that it’s “long term.”

Storey wouldn’t comment on the terms of Rich Energy’s deal with Haas to Jalopnik, saying they’re confidential because they’re commercially sensitive.

The Haas team, when asked about Rich Energy, told Jalopnik via email that its “due diligence of potential partners is a confidential matter,” and that Rich Energy is simply a title partner—it has no stake in the team.

Steiner took a similar tone about the confidentiality of the deal soon after it was announced, with Autosport writing that he “refused be drawn on whether Rich Energy’s money would be ‘extra’ funding, or would simply allow Haas to scale down his own investment, but stressed there was no plan to expand the team.”

The Offices

Jalopnik reached out to businesses that consult startups like Rich Energy, individual consultants, finance professors and other financial experts to get an expert opinion if any of what Rich Energy is doing is out of the ordinary, particularly with regards to where its businesses are set up. None were willing to go on the record with their take on Rich Energy as a business and as an F1 partner, mainly because of the lack of information out there about the company.

As for what we do know, Rich Energy is an international amalgam in terms of location, even with its UK brand. It has offices and trademarks registered in Croatia and the UK, and the product is manufactured in Austria and distributed in London.

The Rich d.o.o. copyright was registered by Majstrović in Croatia eight years ago, and the address of the trademark is listed as Podravska ulica 20, Osijek, Croatia, which appears to be residential.

While it’s not uncommon that a trademark is registered to a residential address, Majstrović’s different businesses and trademarks are registered in different locations

His medical-research organization, for example, is located in a nondescript, older building in Vukovar whose Google Maps photos from 2012 match the date of the company’s founding. The March 2012 building street view shows signs that, when translated from Croatian, say “doors and windows,” something about a new address, and appear to advertise financing options. His goods exchange was registered in a shopping center in Osijek.

Then, there’s the UK location. The UK trademark is registered at Hyde Park House, 5 Manfred Road, UK, which is essentially the office equivalent of an apartment complex.

Office spaces are available to rent for individuals and businesses there, but Rich Energy isn’t listed as a business hosted by the location, according to a database that pulls from Companies House data but has a disclaimer about errors. We’ve attempted to confirm whether Rich Energy is a renter, but haven’t heard back.

Storey told Jalopnik the Manfred address is just the registered address where an accountant is—something he said is “very common in the UK”—and that the company has two other office locations it makes use of in London.

The CEO’s Rocky Past With Other Business Attempts

Storey is listed as an officer of six companies in the Companies House registry, and looking into them gives some good context for understanding Rich Energy.

Three companies are listed as active: Rich Energy Racing, Rich Energy and Wise Guy Boxing, the last of which listed boxer Frank “The Wise Guy” Buglioni as a director. The others—Tryfan Technologies, Tryfan LED and Danieli Style—are listed as dissolved. Many haven’t done well monetarily, and have been involuntarily removed from the registry or wound up as a result of debts.

It’s also worth noting that in all but the Rich Energy Racing filings, where his occupation is registered “CEO,” Storey is listed as a computer consultant.

Buglioni, removed as a director from Danieli Style and Wise Guy Boxing in 2015, told Jalopnik via email that he “elected to remove [himself] from association” with Storey because he “didn’t support William’s business strategies.” Buglioni didn’t comment further.

Danieli Style most closely mirrors Rich Energy, attempting to create a presence in a sport through promotion, sponsorship, and semi-famous ambassadors, as evidenced by its Twitter account with 35 posts and its two now-defunct domain names. It lasted a few years, from 2013 to 2016.

But, of course, that’s not indicative of how Rich Energy is going to do, and Storey sees past failures as part of life as an entrepreneur.

“Not everything’s going to be a smash hit,” he told Jalopnik.

The People Involved With Rich Energy

Rich Energy all seems to start with Majstrović, the Croatian entrepreneur who registered the trademark in 2011 and whose businesses have included everything from medical-records companies to energy drinks. He’s listed as the owner of Rich d.o.o on LinkedIn.

Majstrović is tough to track down. His online presence really only interacts with Rich Energy content, and coverage of Majstrović is often centered on his Osijek goods exchange. But a brief blog from mojzagreb.info from 2011 tied Majstrović with something called Party League Croatia, an initiative to promote Croatia as a hip tourist country with a lively nightlife scene (emphasis ours):

In Zagreb, Party League Croatia will be presented on June 29 at Ban Jelacic Square, then in Rijeka, Pula and Hvar, and the final party will be held on July 13 in Dubrovnik. At Party League Croatia will be promoting new energy drink Rich, designed by Osijek entrepreneur Dražen Majstrović and famous athlete and caterer Alen Borbas. Realizing that there are only foreign brands in our energy drinks market, they have worked with experts to create an original Croatian recipe but also a recognizable visual identity.

After that, Rich Energy seemingly fell off the face of the earth for a few years. When it returned, it was with CEO Storey expressing interest in buying Force India prior to it going into administration.

Interestingly, Storey’s promotion of the brand is similar to that of Majstrović’s. Namely, it talks up the creation of a national energy drink—but in the UK, not in Croatia. Here’s the company description, from Rich Energy’s website:

Rich Energy is a premium and innovative British energy drink painstakingly developed and optimised over the last 6 years with leading beverage experts and recently launched in the UK and US. [...]

We worked with leading experts around the world on all elements of this fantastic product and we are very proud to bring the elevated taste and experience of the UK’s premium energy drink to the market. Get Rich and enjoy the experience!

Storey has claimed in the past that Rich Energy gained its name due to its base in Richmond, London, England, but told Jalopnik the name was, in reality, “sort of serendipitous”—it was trademarked as “Rich” in Croatia back in 2011, and Storey picked it up and rebranded it all “from scratch.”

“I bought a liquid and a drink from which I then created the brand,” Storey said. “They had a word mark “Rich,” which has a slightly different meaning, shall we say, and we said, ‘Right, okay, we can work with that, but we want to completely change the whole brand.’”

The stag logo is also said to reflect the deer that live in a park in Richmond, according to the Daily Telegraph—interesting, considering reports of Whyte Bikes suing Rich Energy over its logo in February.

A History of Questionable Sponsors in Formula One

Formula One is no stranger to unconventional sponsors. Belgian financier Jean-Pierre Van Rossem stunned the world with the “groundbreaking” Moneytron machine, which he claimed was a supercomputer that could supposedly predict stock market trends. Moneytron sponsored the Onyx F1 team, only for the thing to turn out to be a scam. There was T-Minus of Nigerian Prince fame and Leyton House. There was the Andrea Moda Formula team, disqualified for being too dangerous before owner Andrea Sassetti was arrested for forging auto part invoices. Sulaiman Al-Kehaimi posed as a Saudi prince and promised to purchase a huge stake in the struggling Tyrrell Racing team before being arrested as a fraud. While he was acquitted, the struggling Tyrrell eventually succumbed to the loss of a stable financial backing.

Of course, suspicion is natural with sponsors that are hard to pin down—even with F1’s most successful teams—given the series’ past and present. Just a few months ago, tobacco company Philip Morris tried to play coy with its “Mission Winnow” brand sponsorship of the Ferrari team, promoting a vague allusion to vaping before getting pulled off cars before this year’s first race. That’s a story in itself.

Rich Energy doesn’t perfectly mirror any of these examples. It has produced tangible products—albeit ones that are difficult to locate—and Storey claims tangible sums of money in the bank and tangible manufacturing facilities. But if the partnership falls through, it wouldn’t the first time.

When it comes to Rich Energy and those involved with the company, there’s quite a bit of public information—just not enough to get a concrete read on the company. Its CEO insists that said information doesn’t tell the full story, and that people are looking at his company “the wrong way.”

“I’ve been rather puzzled as to why people have been suggesting that there’s anything wrong with us or anything like that,” Storey told Jalopnik. “It’s quite the opposite.

“Rather than saying, ‘Blimey, this company has, in under four years, grown this quickly, well done,’ they’re saying, ‘Oh, there must be something wrong.’ Well, there’s nothing wrong at all.”

So, what is Rich Energy? Rich Energy, like many other companies, is whatever it wants us to see—the F1 liveries, athletes, online influencers and talk about how it’s doing things no other company has done before. Aside from that, it creates a lot more questions than answers.

But Storey doesn’t seem to mind much.

“People are sort of scratching their heads: ‘Who are Rich Energy? How are they doing these things?’” he told Jalopnik. “In a way, that’s a compliment to us.”