Honus Wagner’s career hung in the balance. In 1901, the superstar shortstop was in his second season with his hometown Pirates. But a wrenched knee suffered on the turf at Exposition Park—the Pirates’ home on the north side of Pittsburgh, a few hundred feet from where their current stadium stands today—along with rheumatism threatened to send him back to the coal mines from whence he came as a promising semipro ballplayer less than a decade earlier.

He was told he was getting a visit from “Bonesetter” Reese, a millworker-turned-healer from Youngstown, Ohio, just across the state line. “I never heard of him,” Wagner recalled decades later. But Reese stormed in and cleared out the locker room, even throwing out team trainer Ed LaForce.

He was a tall man with a mustache (contemporary accounts said he resembled Mark Twain), enormous hands and deep blue eyes—so deep that Wagner said he thought he was going to be hypnotized.

“Bonesetter” had earned his nickname in his native Wales. (It was somewhat of a misnomer. He didn’t actually set broken bones.) Although Major League Baseball was in its infancy, Reese was already acquiring a reputation as the last-ditch healer for major league ballplayers who wanted to stay on the field and for whom all other treatment had failed, the Dr. James Andrews of his day.

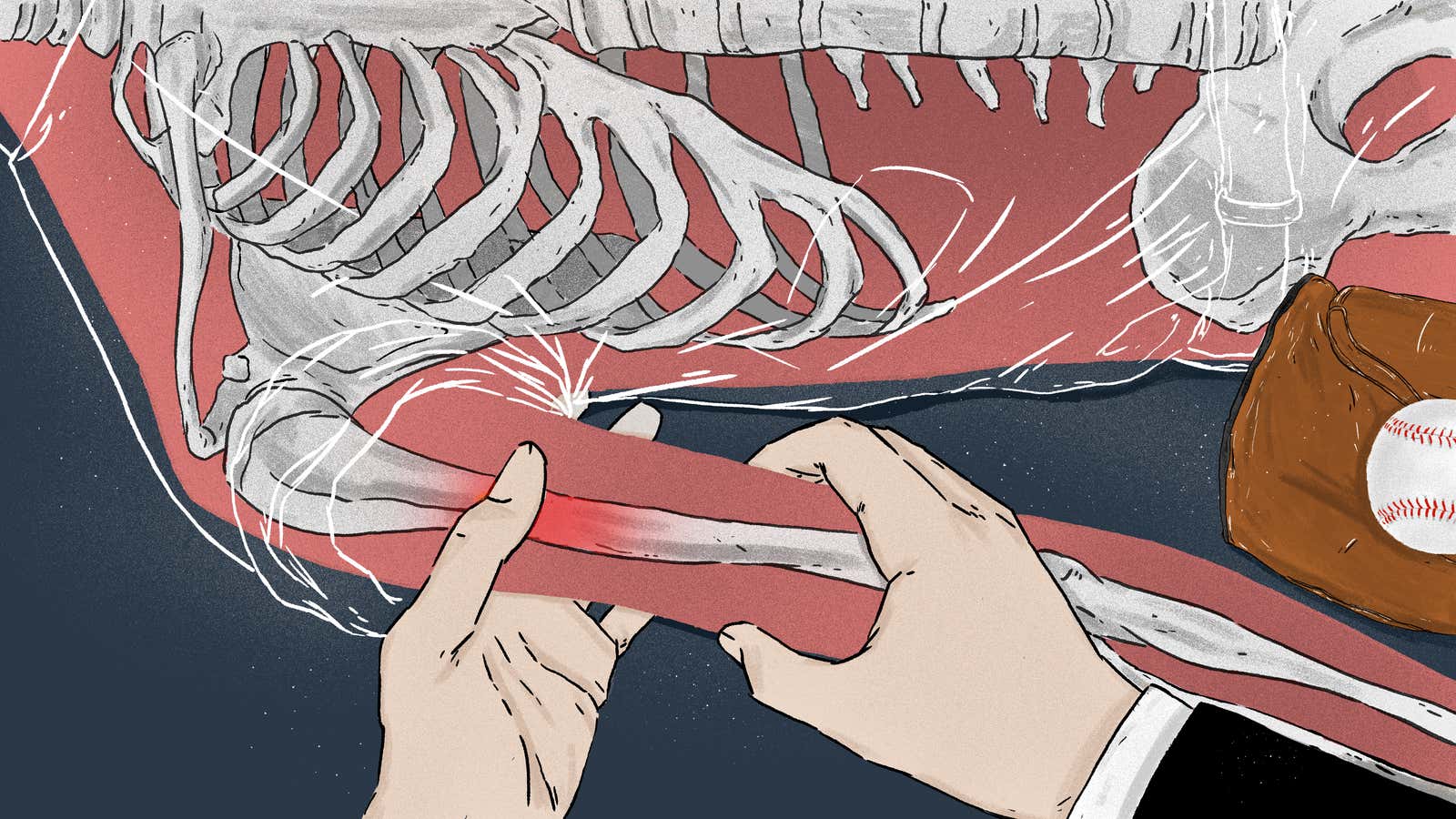

“He had me stretch out flat on my back and he tried to work my left leg up around my shoulder, like a contortionist,” Wagner recalled. “I thought he’d cripple me and wouldn’t relax. For about 30 minutes, he tussled and then I gave in. He punched me everywhere but on the sore spot. ‘Now walk,’ he commanded. I told him I couldn’t. ‘Sure you can,’ he answered. The first thing I knew, he gave me a push and I walked. In fact, in a day or two I was back in there good as ever.”

Wagner, of course, went on to be a member of the Baseball Hall of Fame’s inaugural class, and was immortalized in cardboard—the most expensive baseball card ever made—and in bronze—a statue erected before his death at Forbes Field, then moved to Three Rivers Stadium and now PNC Park. Reese has mostly faded into obscurity. But in his day, and for decades afterward, as long as there were old-timers who remembered him, he was celebrated as a healer and celebrity.

Reese’s trip to Exposition Park was a rare one. He preferred to stay in Youngstown and see patients at his home, including the greatest athletes of their day. “If it hadn’t been for the wizardry of Bonesetter Reese, who fixed my arm in 1927,” said hall-of-fame pitcher Red Ruffing during a swing through Youngstown, “I wouldn’t have had a big-league pitching career.”

He was hardly the only player who could make that claim. How much emptier would Cooperstown be without Bonesetter Reese?

John David Reese was born on May 6, 1855, in Rhymey, Wales. His father William died a year and a half later, and his mother Sarah died when he was 11. He was taken in by a local family and like so many young men in Wales, went to work in an iron mill.

Ironwork had become one of the nation’s most prominent industries, as tools and weapons were supplied to the British while their empire was in full bloom. The man who took Reese in, Tom Jones, was also a “bonesetter,” sort of a proto-chiropractor that practiced massage and manipulation to heal strains and dislocations. “My manipulation is something similar to that of an osteopath,” Reese was quoted many years later as saying. “The theory on which it is based is that muscles and ligaments become displaced and remain so until put back where they belong.”

Reese’s mentor Jones came from a long line of bonesetters, and throughout Reese’s career, there always seemed to be whiffs of mysticism associated with him and his profession. For his part, Reese, a deeply religious man who taught Sunday school, believed he was practicing “a godly craft” with talent bestowed from the Almighty. “He knows his Bible better than most medical men know their Materia Medica,” the Youngstown Vindicator wrote of him in 1930.

In 1887, Reese came to America, and ended up in Youngstown, then a small town in Northeast Ohio near the Pennsylvania border. Youngstown sits atop a coal seam, and mining jobs and ironwork drew scores of Welsh immigrants there in the 19th century. Reese went to work in one of the area’s rolling mills when one night, one of his colleagues was injured. Reese put his hands on him, and pretty soon, the co-worker was back at his post. It was the start of his medical career. He’d work nights at the mill and spend his days taking on patients, many of whom were his co-workers, or employees at the other mills and factories that started to dot the banks along the Mahoning River.

Reese claimed in an interview later that he’d seen so many patients in addition to his regular job at the mill, he was only getting eight hours of sleep—a week.

“So many people kept coming to me, that I could not do both,” Reese recalled. “Knowing people would keep coming to me, I gave up the mill.”

Reese left the mill for good in 1894 and started seeing patients at his home. He told those he saw to pay whatever they could. This was an extraordinarily charitable move by Reese, who by all accounts was a humble, decent man. It was also a savvy one. Reese was not a licensed physician, and the local medical community was incensed at his practice and tried to stop it. Reese did everything he could to try to comply while still practicing his craft. Throughout his medical career, he was quick to refer potential patients to doctors, knowing full well the limitations of his skills.

Reese even went so far as to enroll at the Case Institute (now Case Western Reserve University) in Cleveland to get medical certification. But that lasted about a week. The sight of blood made him queasy.

Ultimately, Reese had accumulated enough friends in high places that the governor, Asa Bushnell, interceded on his behalf and the Ohio General Assembly passed a law specifically to license Reese, allowing him to continue to practice his brand of medicine.

Reese’s practice was so successful that in 1902, he was able to move to a home on Park Avenue on Youngstown’s fashionable, tree-lined North Side. The address became well-known to cab drivers, who found themselves shuttling patients who had arrived at one of the city’s train stations from across the nation. (The house, at the corner of Park and Ohio avenues, facing Wick Park, still stands today, but has been split up into apartments.) Reese’s neighbors included the Renners, a prominent beer brewing family who built an enormous Greek-influenced mansion, including a billiard room where son Emil (known as “Spitz”) could practice on the way to becoming one of the top amateur players of his day. And Reese lived not far from a family of Jewish immigrants, whose Polish last name had been anglicized to Warner. Four of the family’s sons started showing movies around town, and parlayed that into a multi-billion-dollar media company.

As word of Reese’s skill spread, patients from all walks of life started to seek him out, including another Youngstown native named Jimmy McAleer.

McAleer played primarily for the Cleveland Spiders, a team which flowered into existence in 1887, joined the National League two years later, and then were one of the teams blinked out of existence in 1899—along with Wagner’s first team, in Louisville. McAleer was heralded for his speed and grace in the outfield and on the basepaths, but a charley horse had laid him up for some time. Treatment by Reese brought him back to form, and soon, he was recommending Reese to all of his ballplayer friends.

Soon, baseballers were beating a path to Reese’s door. The Society of American Baseball Research compiled an All-Star team of players treated by Reese, including Ty Cobb, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and Tris Speaker in the outfield; Home Run Baker at third base; Napoleon Lajoie and Rogers Hornsby at second; and a pitching rotation including Cy Young, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson, Ed Walsh, Addie Joss and Grover Cleveland Alexander. Franklin P. Adams waxed poetic about the Chicago Cubs’ infield of Tinker to Evers to Chance; Bonesetter Reese treated all three.

But of all the ballplayers Reese saw, the most of famous of the era eluded him. Reese told a reporter from St. Louis that he’d never treated Babe Ruth—but the Babe had given him an autographed baseball.

Reese treated boxers including Jack Johnson, Battling Jones, and Gene Tunney, and was in attendance at Tunney’s victory over Jack Dempsey at Soldier Field. (It’s unclear where he sat, but he could have been one of the “titans of the world” filling the first 10 rows that promoter Tex Rickard boasted about.) He treated Gertrude Ederle, the famed “Queen of the Waves” who in 1926 became the first woman to swim the English Channel.

Reese was also known for his work with entertainers, who came to see him while performing at one of the circuit’s stops in Youngstown. At Reese’s death, the manager of the Palace Theater in Youngstown estimated that Bonesetter had worked on at least 1,000 chorus girls and acrobats in his career. In fact, a grateful RKO Pictures, formed from the Keith-Albee-Orpheum chain of vaudeville and live theaters, bestowed upon Reese a lifetime pass good to any Keith theater in the United States or Canada.

Another patient was Will Rogers, who in 1926 opened Stambaugh Auditorium, a large community gathering place on Fifth Avenue. Reese walked the three blocks for the opening event, and although he treated patients wearing a coat and tie, he apparently hadn’t dressed up as nicely as this situation called for—and then was mortified when Rogers called him up on stage to be recognized.

His patients extended to the world of politics as well, including Theodore Roosevelt and British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who asked for Reese’s services after an American tour left his hand throbbing and sore after shaking thousands of hands.

Reese also treated George “Papa Bear” Halas, who played baseball in the 1910s in addition to his more celebrated football career. In fact, Halas had to take pains to identify himself as a baseball player; Reese eschewed treating football players, saying they were likely to not follow his orders.

“He felt my derriere,” Halas recalled in his autobiography. “‘When you slid into third base,’ he said, ‘you twisted your hip bone. It is pressing on a nerve.’ He pushed his steely fingers deep into my hip, clasped the bone and gave it a sharp twist. The pain vanished. I danced out of his office.”

Three days after Thanksgiving in 1931, Bonesetter Reese died at his home at the age of 76. He’d been seeing patients almost until the end, his only concession being that he couldn’t take on spinal cases any more, as they were too arduous. Hundreds, including many former patients, turned out for his burial several days later in Oak Hill Cemetery—not far from the grave of the man who bore some responsibility for his fame, Jimmy McAleer, who’d died earlier that year.

“The work of the Bonesetter is ended,” the Vindicator wrote after his death. “There is none to take his place.”

In one sense, that was true. Reese represented the apogee of a distinct skill set that was falling out of favor as medical science progressed.

But Reese’s role, if not his practices, became a permanent part of clubhouses. Ultimately, visits to Youngstown to call on the Bonesetter were replaced by team physicians and trainers on staff. Bonesetter Reese’s name remained a byword long after his death, thrown into columns during Hot Stove season by old-timers recollecting the man who kept players on the field in the early days before sports medicine became its own industry.

Bonesetter Reese could have been the first. Seeing his work, Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss offered him a position on payroll. But Reese was content to stay in Youngstown and let the ballplayers come to him.

Vince Guerrieri is an award-winning journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He likes Lake Erie perch sandwiches, Jim Traficant and long walks on the field at League Park. His website is vinceguerrieri.com, and you can follow him on Twitter @vinceguerrieri.